Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Jan-30-2008 23:50

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

Everyman`s Greed: Corruption in China

OOI Keat Gin Salem-News.comIf only every politician, every ruling government adhere to this revelation: ‘The world has enough for every man’s needs but not every man’s greed’, then, and only then, will the disease of corruption be truly eradicated.

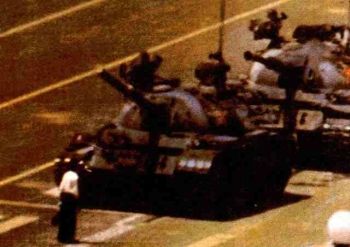

Image from Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 Courtesy: betterknowanoble.blogspot.com/ |

(PENANG, Malaysia) - When we speak of corruption, the most common manifestation is of a corrupt public official taking bribes in return for favors.

For instance, a custom officer allowing a shipment of goods to pass through a checkpoint without further examining the goods apart from perusing the manifest and stamping it as a sign of approval or clearance consequent of him being given a certain consideration from importers of the aforesaid consignment, or the case of a judge making a decision favoring a certain party because they (the favored party) prior to the judgment had transferred a significant amount of funds to the judge’s bank account in a foreign country (to avoid suspicion or detection).

Countless similar examples can be cited but suffice to say corruption comes in many forms and guises. Controversy abound in situations where certain practices that are deemed to be corrupt acts in one socio-cultural context may be seen in a different light in another socio-cultural setting, perhaps even accepted and acknowledged as traditional practices hence no qualms whatsoever to the parties involved. ‘Grease money’ is a common term used in many countries and society to denote the monies exchanged overtly or discreetly to ensure the smooth execution of a proceeding. ‘Tea money’ or ‘coffee money’ similarly used to smooth operations.

No nation, no society, whether in the past or in contemporary times, escape the baneful effects of corruption in its various manifestations. Corruption can be said to be as old as History; the latter has witnessed the former repeating and recurring again and again despite the dire consequences that befell those who were caught with their hands in the cookie jar.

China that boasts of an ancient tradition that stretched over five millenniums has corrupt practices recorded throughout its history. Corrupt officials and oppressed peasantry are common and popular themes in novels, theaters, moral tales, and had entered folklores. A typical scenario is of a righteous but poor farmer after having been wronged by a rich man attempt to seek justice at the local court where the magistrate, who had been heavily bribed by the rich man, ruled against the farmer. Punishment is meted out by the court and the farmer while in jail realized that justice has a price that he, being poor, was unable to pay.

China’s sorrowful record of corrupt officials and corruption that pervades practically all spheres of life of the common people could be traced to the traditional Confucian system of governance. Although the selection of officials through a system of scholastic examinations to serve the emperor and to administer a huge empire was not specifically the sage’s idea, the best candidates steeped in Confucian teachings became the scholar-bureaucrats, what became known to Westerners as the mandarin class.

According to Confucian belief, a scholar who succeeded to be appointed a public official to serve the emperor was indeed a great honor to himself but more importantly to his family and clan. Families whose sons were appointed scholar-bureaucrats earned great respect and reverence to the family, ancestors, and all clansmen. To be able to serve one’s emperor and realm was the highest achievement a man could aspire. Confucian tradition maintained that honor bestowed on the scholar-bureaucrat outweigh any material returns; in fact it was expected that a scholar-bureaucrat served his emperor and country selflessly without expecting any material rewards for such sacrifices.

Therefore salaries of public officials were kept to a nominal rate; ideally a scholar-bureaucrat was regarded as a servant to the emperor and country utilizing his intellectual expertise to ensure smooth administration where heaven and earth are in equilibrium where the son-of-heaven (emperor) presided. Scholar-bureaucrats serving in the provinces and districts functioned as administrators including as tax-collectors, magistrates and judges, head of security (local police chief), public health officer, city mayor, and carried out numerous responsibilities.

He has a staff of minor officials that he appoints to carry out all his duties. At times of war or rebellion, this civil official has to liaise with the local garrison commandant; if both were of the same rank the civil official overrides his military counterpart. Scholar-bureaucrats were all-powerful men even deciding on the fate of life or death of the common people.

But it was this nominal compensation for serving the emperor and the country that provided the pretext for scholar-bureaucrats to accept gifts and other material comforts from the people. Initially the peoples’ practice of bearing gifts was noble intended to help the official with little comforts of life. However, inevitably some individuals used the gifts as bargaining chips for currying favors from the all-powerful government official. Gradually the ‘gifts’ became mandatory and accepted as traditional practice when approaching an official.

Peasants brought with them foodstuffs and even livestock as gifts. Merchants might present a chest of gold or silver money to the presiding magistrate ensuring that his judgment swayed in favor of the gift-bearing party. Now and then one hears of upright officials who refused such gifts but these righteous scholar-bureaucrats were not the norm but the exception and minority. The majority, however, happily welcomed such gifts and would be annoyed and even vindictive if the presentations were not up to his expectations.

The face of corruption become rife and open towards the waning years of a dynasty when central authority begins to loose its grip on the outlying provinces. In fact owing to the great distances between the capital and the frontier provinces, officials in charge of the latter for the most part were left to their own device with scant supervision. In the early years of a new dynasty, a sort of ‘cleaning house’ policy will be implemented with senior imperial officials and censors being sent to all the provinces to weed out all ‘deadwood and weeds’ (the notoriously corrupt, the inefficient, the indolent, the drunkard, and the likes). Such ‘cleaning house’ operations often last a decade or less; when the dust from the broom settles, all the old ways return and it is ‘back-to-business-as-usual’.

Furthermore the Confucian precept of leadership through example expects the emperor to be an exemplary leader. History, however, has shown that only a handful could be said to fit the Confucian criterion of an exemplary leader. Therefore when a pleasure-loving son-of-heaven sits on the dragon throne, he neglects his official duties. A carefree emperor breeds a carefree bureaucracy. Consequently upright officials lost faith in the system; some turned to drink, others turned to poetry or other intellectual pursuits; ironically they too neglect their responsibilities. Minor and lesser officials begin to take charge. Good administration and the welfare of the common people were the last on the agenda of these officials who prioritized the utilization of their official position to amass as much material wealth that they could get their dirty hands on.

Upright officials accompanied the rise of a new dynasty and when the central authority waned towards the demise of a ruling dynasty, corruption amongst the mandarin class of scholar-bureaucrats become rife and commonplace. This dynastic cycle continued until the collapse of the Ching (Manchu), the last imperial dynasty, in 1912 following the success of Chinese revolutionaries.

The 1911 Chinese Revolution ushered in a new era of corruption. The Nationalist or Guomindang (Kuomintang, KMT) that assumed power of the Chinese Republic had no ‘cleaning house’ phase unlike previous dynasties. The Nationalist under Jiang Jie-shi (Chiang Kai-shek) from 1925 following the demise of Dr Sun Zhong-shan (Sun Yat-sen) initially had control of only the southern provinces, its power base, whilst the rest of the country was partitioned into various spheres of authority by a score of self-proclaimed warlords. Many warlords clashed with one another or struck alliances against other warlords; the prize of contention amongst the disparate group of warlords was Beijing, the seat of authority where Western powers recognized as the government of China. One warlord after another seized Beijing, and sat on the throne before being toppled several weeks or months thereafter. In this chaotic situation, there was ‘runaway corruption’; every one had a price be it gold, territory, women, opium, and a host of other material indulgences. The Nationalist Chiang was one amongst the many warlords fighting for power and at times even his own survival. Chiang strategically and literally bought over one warlord after another utilizing various means in his northern expedition to reunite the country under the Nationalist banner. By 1927 most of China came under the Nationalist fold ending the era of the warlords. But Chiang’s greatest foe, from the very beginning, was the communists. It was said that when Chiang’s emissary met Zhou Enlai (Chou En-lai) of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seeking to negotiate a ‘price’ for their support and alliance, Chou turned down all offers. When told about this outright rejection, Chiang declared to his senior officials that they had finally met the real enemy.

During the 1920s and 1930s government officials whether under warlords or the Nationalist were corrupt to the extreme, each trying to outdo the other in squeezing the common people and amassing wealth as fast as they could possibly achieve within their often brief and unstable position. They could be replaced, killed outright; it was a time of living dangerously, and any wrong move or misstep might mean life and death.

The outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-45) and the civil war (1946-9) provided fertile ground for all kinds of corruption to thrive. Despite the official declaration of a united front between Chiang’s Nationalist and Mao Zedong’s (Mao Tse-tung) communists to fight the common enemy Japan on Chinese soil, some Nationalist units made a pact (with monetary incentives) with the Japanese to avoid a clash of arms and instead conserved their resources to eliminate their allies, the communists.

From 1941 Britain and the United States supported Chiang and the Nationalist forces with funds and equipment. It gave a golden opportunity to Nationalist officials to siphon some of this support to their personal advantage. When Mao declared the People’s Republic of China in October 1949, the next decades witnessed the weeding and ‘cleaning house’ process to rid ‘New China’ of the vestiges of bourgeoisie corrupt habits and practices. Political commissars came down hard on comrades who exhibited bourgeoisie including the expectations of ‘gifts’ from the people in the course of carrying out their official duties and responsibilities. Such officials were sent for ‘re-education’ at labor camps in remote provinces to rectify their erring behaviors; some notorious individuals faced the gallows.

The hard-line measures including the death sentence were deterrents but they could not completely eradicate the disease of corruption amongst state officials. Gradually the disease manifested itself, bit by bit throughout the entire strata of the huge bureaucracy. Now and then the ‘cleaning house’ process will be implemented.

When Deng Xiaoping’s pragmatic economic policies introduced market incentives and encouraged foreign trade, the decentralization of the economy allowed more latitude for provincial officials. The market economy provided greater opportunities for government officials, despite professing communist ideology and Mao Zedong thought, to line their personal pockets. Liberalization and decentralization of the economy witnessed a relaxation of central control; greater autonomy translates to greater ‘extra-curricular activities’ on the part of officials. The ugly head of corrupt practices gradually emerged.

Reports of corrupt officials being sent to the gallows increased as the economy started to heat up in the 1990s and 2000s. For every official caught with his hand in the cookie jar, there are hundreds under investigation and thousands yet to be suspected or detected.

It is indeed a tall order to expect a huge country like China to be administered by an army of upright officials. No country in the world, east or west, north or south, possessed a civil service free from corruption; neither to be found in the past, the present or the future. It is naive to think and expect such an ideal situation. If only every politician, every ruling government adhere to this revelation: ‘The world has enough for every man’s needs but not every man’s greed’, then, and only then, will the disease of corruption be truly eradicated. Hence while this ideal or Utopia has yet to come to pass, it is every citizen’s responsibility in his country to ensure that the degree of corruption is kept low and contained.

Activists could play a pivotal role in combating corruption. In China, as well as elsewhere, activists faced an uphill climb. They are in fact fighting human nature as greed is a human failing. Religious teachings might temperate man’s greed but it only has effects on those who have faith in a particular religion. Those out of the loop, the non-adherents of that religion, will have no qualms whatsoever in committing the so-called sinful acts or fear the damnation prescribed. Religion, however, has little headway in atheist China. Activists need the concerted effort of moral and spiritual arguments against corruption to be effective in their struggle. But without the concerted effort with government authorities, it is indeed protracted and difficult struggle. However, what can be seen in the past decade is the political will on the part of the Beijing leadership to wield a deterrent blow on corrupt officials even utilizing the rather harsh death penalty on the guilty. An effective re-education program for the convicted is a better option and is currently being carried out; capital punishment as a deterrent remained questionable.

OOI Keat Gin is an associate professor and coordinator of the Asia-Pacific Research Unit (APRU) in the School of Humanities, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia.

Articles for January 29, 2008 | Articles for January 30, 2008 | Articles for January 31, 2008

googlec507860f6901db00.html

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

[Return to Top]

©2026 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.