Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Oct-06-2011 23:32

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

The Three Centuries of San Miguel

Kent Paterson for Salem-News.comWhether old-timer or newcomer, the residents of San Miguel take pride in their annual fiesta in honor of St. Michael.

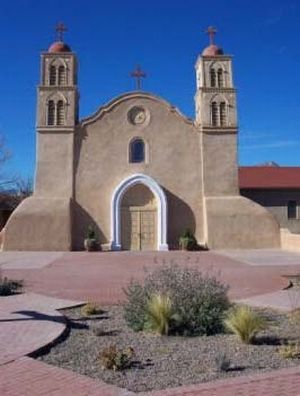

Courtesy: San Miguel Catholic Church |

(LAS CRUCES, N.M.) - An old rural town just south of Las Cruces, San Miguel is a small community that could be overlooked by drivers headed elsewhere. Yet a stop in the town reveals a treasured past that tucks in varied cultural influences, distinct waves of migration and epochs of economic growth and contraction. The following story is part of Frontera NorteSur’s special Centennial of New Mexico Statehood series and is made possible in part by grants from the New Mexico Humanities Council and the McCune Charitable Foundation.

Driving south of Las Cruces on Highway 28, travelers pass through the shady canopy of Stahmann Farms’ pecan forest before gliding into the small town of San Miguel. There, along the few blocks of old abode buildings and signs for fresh farm produce, day trippers might very well encounter friendly folk like Mike Otero.

A federal government retiree, Otero stands outside the striking stone façade of the San Miguel Church reminiscing about decades past and his wedding at this very place in the 1950s. Originally a mountain boy from the village of Manzano in north-central New Mexico, Otero says his real first name is Miguel but everybody just calls him Mike.

After completing military service in Korea, Otero came to Dona Ana County to work at White Sands Missile Range, where he soon met a young woman named Dora from San Miguel. The couple exchanged vows at the historic church and raised a family during a time when Dona Ana County was transitioning from a rural, agricultural-oriented county into part of a border metroplex with a growing university and an expanding federal government presence.

In mid-twentieth century New Mexico, the winds of change also swept Otero’s hometown of Manzano up north, scattering his family to bigger and upcoming places. And the former federal worker’s daughters became professionals in the medical and educational fields.

Nowadays, Otero’s children and extended family might work in El Paso, live in Albuquerque or reside in Oklahoma City. “That’s the way it is,” Otero lets out with one of his hearty laughs. “I got relatives all over.”

|

For such a small town, the genealogical pathways in and out of San Miguel are surprisingly long and deep. Old-time Hispano families trace their ancestors back to the time of the US conquest of the 19th century. An important group of locals hails from the generation of Mexican immigrant workers who labored on nearby Stahmann Farms in the 20th century. A newer segment of townspeople has arrived in the 21st century.

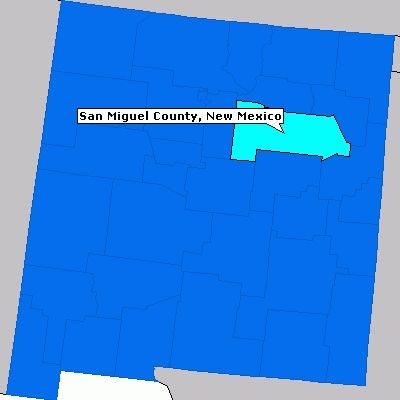

Dennis Smith, GIS specialist for Dona Ana County, estimates “somewhere between 1,300 and 1,500” people lived in unincorporated San Miguel at the time of the 2010 Census. Besides a handful of businesses, San Miguel contains a non-profit rural health clinic and an elementary school operated by the Gadsden School District.

Whether old-timer or newcomer, the residents of San Miguel take pride in their annual fiesta in honor of St. Michael. Held to raise funds for the town’s Catholic Church, the fiesta is held on the same late September weekend as the Whole Enchilada Festival just up the road in Las Cruces.

While the Whole Enchilada bash has grown into a massive affair that receives international attention, the San Miguel Fiesta remains a low-key event, barely advertised and perhaps drawing three or four thousand people over the course of two days, according to longtime resident and fiesta organizer Manuel Leyva.

At the San Miguel fiesta, Spanish and country music intermingle and dance into the early fall evening. New Mexican, Mexican and European-style foods stir many a palate. Gorditas, burritos, menudo, churros, and the beloved sopapillas with red chile and honey are all for devouring at affordable prices. The jalapeno peppers stuffed with cream cheese and bacon drip with the morsels of different cultures.

The fiesta has changed locations, activities and flavors over the years. Carmen Martinez says her grandmother and other relatives helped build San Miguel’s Catholic Church, constructed with lava rock and finished in 1937. According to Martinez, her relatives hauled the rock from a nearby mesa with horse-drawn wagons. Once held off church grounds, Martinez says the fiesta used to include a softball tournament and allow alcohol consumption.

An 83-year-old Korean War vet, Victor Beck Martinez has old memories of the fiesta. As a young child, he recalls seeing musicians playing the guitar and violin while festival-goers jammed into an old trailer for bingo games. In the early 1960s, the locals contributed sweat equity and construction materials to build a new church parish hall, he says.

The Mesilla Valley resident has been to practically every fiesta in his time, except during his service in Korea. Yet even in the height of conflict, San Miguel harkened. “I still remembered San Miguel,” Beck Martinez adds, a deep intonation of respect vibrating in his voice.

A neighbor of Beck Martinez, Cliff Barber moved full-time to San Miguel from San Diego in 2007.

“It’s a joy living here, and the neighbors help each other without hesitation,” Barber says. “It’s a wonderful place to live.” Standing alongside his lanky neighbor, Beck Martinez quips, “I’m trying to make him a native.”

While eschewing the hot chile varieties many New Mexicans cherish, Barber admits he’s grown used to at least the milder peppers and even craves them. “It’s kind of an addiction,” the transplanted Californian says. “If you don’t have a chile in a day, you kind of miss it.”

The 21st century version of the San Miguel Fiesta features newer elements like a horse show and the Latin American sea food dish of ceviche- fish cooked up in lime juice. Held on church grounds, today’s fiesta does not offer alcohol.

Deacon Emilio Ramos is among the many individuals helping to annually reinvent San Miguel.

The Mexico-born Ramos pursued a US military career, retiring after 34 years of federal service before getting ordained three years ago. Ramos was subsequently assigned to administer the San Miguel Church and a second one in nearby Mesquite for the Roman Catholic Diocese of Las Cruces.

A visitor to regional celebrations, Ramos says he keeps an eye out for different activities that could be incorporated into the San Miguel fiesta. The ex-serviceman’s experience in organizing events for his military squadron is also put to use at fiesta time, he says.

|

“I’m very pleased to be here serving the people of the two communities. I’m very happy with the fiesta and the things that are going on,” Ramos says of his work in San Miguel and Mesquite. “They go all out with the celebrations, the different activities. The fiesta just brings everybody together at one point and one time in the year.”

Like celebrations and holidays in other traditional New Mexican communities, the San Miguel Fiesta is occasion for the re-gathering of the diaspora, a time when people return from Arizona, Texas and elsewhere for a weekend of family roots.

Historically, farming has been an underpinning of San Miguel’s local culture and economy. Crops grown over the years include cotton, chile, onions, tomatoes, alfalfa, pecans and more.

As a young man, Manuel Leyva bought a small piece of property which was planted in alfalfa at the time. Leyva married a woman whose Mexican immigrant father worked as a foreman for Stahmann Farms. On his five acres, Leyva planted 250 pecan trees. But this year has been a rough one for Levya and other farmers who normally draw water flowing from the Rio Grande.

“The only problem is that there is no water,” Levya laments. “Hopefully my trees won’t die and I’ll have a lot of firewood…”

In southern New Mexico, the Great Drought has now overlapped with the Great Recession. Inter-state water politics also enters into the picture.

“The water that you see going down the river at one time is for Texas, and I don’t understand why there’s no water for New Mexico,” Leyva says.

A 2008 agreement involving the Bureau of Reclamation and irrigation districts in New Mexico and neighboring Texas resulted in the Texans getting more Rio Grande water than prior to the agreement, according to the New Mexico state attorney general’s office. Last August, the state attorney general filed suit against the agreement.

In a recent op-ed, Gary Esslinger, longtime manager of the Las Cruces-based Elephant Butte Irrigation District, took issue with the lawsuit and defended the 2008 deal as a “well-thought out compromise” that protects the ability of New Mexico farmers to pump groundwater in times of “severe drought.”

In order to survive, Leyva and fellow farmers are indeed resorting to groundwater. “I just happen to have a little domestic well and that’s what I’ve been doing to irrigate my trees,” he says. “It takes me two or three days to do it, but it’ll do the work.”

Recently, Leyva and 15 families filed an application for a state permit to drill a new well.

In his long life, Leyva has witnessed many other changes in San Miguel and Dona Ana County. In the 1970s, Levya served two-terms on the Dona Ana County Commission. Back then, he says, the elected body consisted of three commissioners instead of the five who are seated today.

>From San Miguel, Levya represented a huge stretch of territory running from Sunland Park outside El Paso in the south to Garfield in the Hatch Valley in the north. The one-time politician says landfills, funding for volunteer fire departments and improving the salaries of low-paid county employees were the big issues of the era.

Despite many changes, one institution that’s survived the years is the San Miguel Church and its annual September fiesta. Leyva says money from this year’s event could go towards the eventual purchasing for a new roof to cover the outside grounds of the parish hall and make it easier and more comfortable to stage community events.

Frontera NorteSur: on-line, U.S.-Mexico border news

Center for Latin American and Border Studies

New Mexico State University

Las Cruces, New Mexico

Articles for October 5, 2011 | Articles for October 6, 2011 | Articles for October 7, 2011

Quick Links

DINING

Willamette UniversityGoudy Commons Cafe

Dine on the Queen

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

MUST SEE SALEM

Oregon Capitol ToursCapitol History Gateway

Willamette River Ride

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

Historic Home Tours:

Deepwood Museum

The Bush House

Gaiety Hollow Garden

AUCTIONS - APPRAISALS

Auction Masters & AppraisalsCONSTRUCTION SERVICES

Roofing and ContractingSheridan, Ore.

ONLINE SHOPPING

Special Occasion DressesAdvertise with Salem-News

Contact:AdSales@Salem-News.com

Salem-News.com:

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

[Return to Top]

©2026 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.