Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Feb-14-2013 13:45

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

Agron Belica Interviews Jay R. Crook PhD About Afghanistan

Salem-News.comA visual exploration of Afghanistan in decades past.

All images courtesy: Jay R. Crook Ph.D |

(BOSTON) - Recently one of our associate journalists, Agron Belica, conducted an interview with Dr. Jay R. Crook via Skype.

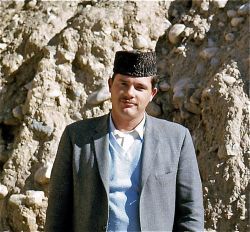

Dr. Jay R. Crook |

The subject was Afghanistan which Dr. Crook had visited several times while living and working in Iran from 1964 to 1980. Though they have been exchanging emails and conversing by telephone for several years, this was the first time they could see each other face-to-face and live, via Skype. The transcript of their conversation begins after the customary exchange of greetings:

Belica: I can see shelves of books and a collection of CDs on the wall behind your head.

(Crook swings the computer screen a bit to the left and right so that Belica can see more of the library.)

Crook: Most of my books in English on Afghanistan and Iran are on the wall to my left.

(Belica nods.) Belica: And all of your slides of Afghanistan are now scanned on your computer?

Crook: Yes, about 1100 in all. Most of them are from my first trip there in the autumn of 1967 when I did a circular tour of the country. I was working on the staff of the Peace Corps program in Iran at the time. I had met a number of Pathans in Pakistan when I was living and working there and had always wanted to see Afghanistan. I took advantage of a five-day regional Peace Corps conference I was to attend being held in the Afghan capital Kabul to use four weeks of my leave time for the tour.

Belica: You said ‘Pathans.’ Who are they? I’ve heard of Pashtuns and Tajiks and Hazaras and Uzbeks in Afghanistan, but not Pathans…

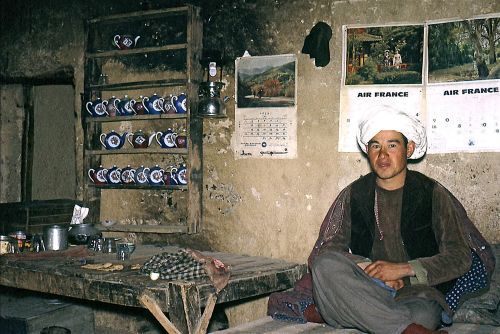

Bamyan tea house |

Crook, smiling: I’m sorry. Having spent five and a half years in Pakistan has affected my vocabulary. In Pakistan, the Pasthuns were, and I suppose still are, referred to as Pathans. The language is Pashtu, but in Pakistan most people say ‘Pushtu.’

Belica: Do you speak Pushtu?

Crook: No, but you can get around most of Afghanistan using standard Iranian Persian which I do speak. In Afghanistan, Persian is called ‘Dari,’ but they are basically sister dialects. In Kabul, occasionally I could use a little Urdu and of course basic English in cities.

Belica, nodding: Dr. Crook, these days all we think of when we hear the word ‘Afghanistan’ is war and death. It’s hard to imagine an Afghanistan at peace.

Crook: Yes, when you look at the pictures on TV news and the grittier postings on Youtube and elsewhere on the net, the emphasis is almost always on war and suffering. Lord Curzon, the British viceroy of India in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—when the British Empire was at it height of world power, much like the American Empire is today—he famously referred to Afghanistan as the ‘cockpit of Asia.’ Of course, he was referring to staging places of bloody cockfights, not the control chambers of airplanes.

(A sudden loud scraping noise suddenly erupts from behind Belica.)

Crook: What is that?

(Belica laughs and nods to the cage hanging behind him.)

Belica: My parakeets. I guess they don’t like us to talk about war.

Crook: Wise birds indeed! It’s too bad that after the two World Wars of the last century and the founding of the UN, war still pollutes the news, but there it is: the eternal folly of mankind. Sorry, Mr. and Mrs. Parakeet.

Belica: Maybe they’ll be quiet if we talk about peace. Could you tell us something about your experiences on your first trip in Afghanistan?

Crook: Well, the Peace Corps conference lasted about five days. During off time from the conference, a few of us went around the sights of Kabul and to the National Museum there, now sadly looted, I understand. We visited Babur’s tomb with its spectacular view of the valley.

Belica: Who was Babur?

Crook: He was the founder of India’s Mughal Empire. He conquered India from his base in Kabul. His great-great-great-grandson Shah Jehan built the Taj Mahal. Babur’s grave is very modest, not grand like those his descendants built for themselves in India.

Belica: The Taj Mahal was built in the 17th century, wasn’t it? When did Babur conquer India?

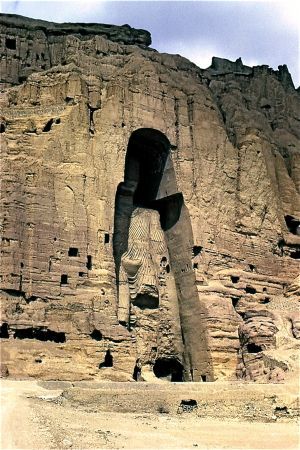

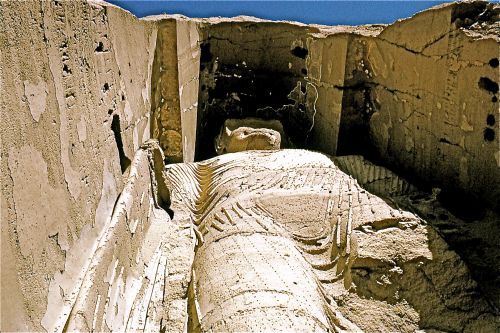

Great Buddha |

Crook: About 1525 or -26, I think.

Belica: So the first Mughal emperor of India is buried in Afghanistan?

Crook nods, then continues: We also visited the city fort called Bala Hisar and the bazaars and ate at some local restaurants. We met some hippies and backpackers who were often searching for themselves in the alleys of the Middle East with the added attraction of cheap hashish. It was an interesting time. No armies banging around the country. Anyway, as soon as the Peace Corps conference was over, I was already itching to see the country. Afghanistan has a lot of fascinating places. Can you guess where I went first?

(Belica knits his eyebrows and thinks a moment.)

Belica: Umm, the Great Buddha of Bamyan?

(Crook nods in affirmation.) Crook: When I heard the news of its destruction, I felt a sad sense of personal loss. Though I am not a Buddhist, I was shocked at the callous sacrilege. Muslims are supposed to learn from history, not destroy it. Does it not say in the Quran: ‘Have they not traveled in the land to see how was the ending of those who went before them? They were more numerous than these and mightier in the remains (they left) behind in the land” [Q. 40: 82] or ‘Travel throughout the earth and see how was their ending’ [Q. 27:69]? How can we learn from the past if we obliterate it?

Belica: Yes. I hear they are doing the same thing in Saudi Arabia, even in the holy cities of Makkah and Madinah.

Crook: It would seem that is the case.

Belica: It is very saddening, but Bamyan had not yet been destroyed when you went there. What was visiting it like?

Crook: As soon as I had finished my duties to the conference, I returned to the Kabul Hotel where I was staying. I hailed a taxi. The driver was surprised by my Persian and asked me where I came from and what I was doing in Kabul. His name was Mohammad Aref. He seemed affable and trustworthy, so I told him that I was planning to go to Bamyan the next day. As I did not have much time, I needed to hire a car and driver. To make a long story short, we negotiated a deal whereby he and his taxi would be at my disposal for the next four days—that is, the duration of the trip to Bamyan—for about 3500 afghanis.

Belica: How much was that in dollars?

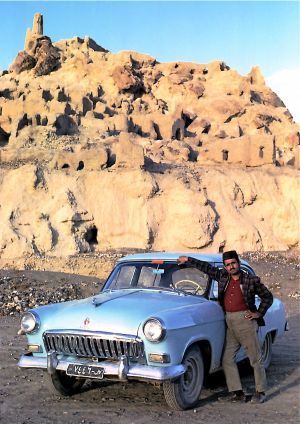

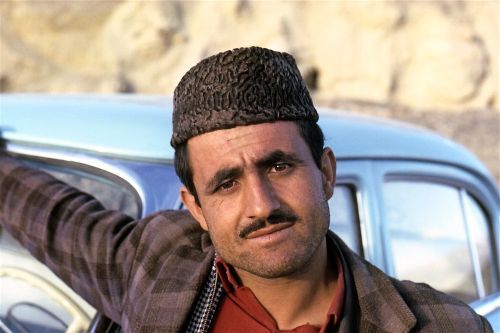

Mohammad Aref and taxi |

(Crook shakes his head.) I don’t remember exactly. Something over $100 back in 1967, I think. Anyway, he picked me up at the hotel punctually the next morning, a Wednesday, and we started out on my first Afghan adventure. The drive was pleasant and Mohammad was informative and pleasant company. I asked him about Afghanistan and he asked me about Iran and America. In those days, the better road from Kabul to Bamyan ran north for about twenty miles on a paved road now called the Asian Highway. We paused for tea and grapes at its junction before turning onto the dusty 50-mile dirt track that would take us westwards to Bamyan.

Belica: What was the drive like?

Crook: Unforgettable. It was like driving from the 20th century back to an earlier time, before the industrial revolution. The Bamyan region is essentially rural and the people of central Afghanistan are mostly Hazaras. Aside from some autos and trucks, there was little obvious evidence of change. The road was rough, so progress was slow and I had plenty of time to absorb the scenery and roadside sights. Flat-roofed villages perched on the rocky slopes of either side of the valley. On the floor of the valley, a broad, shallow stream wound along the track and through fallow farmlands much of the time. As it was mid-October, most of the harvesting had been done. I had plenty of time to people-watch as we passed tents and huts active with village work. We passed men and the occasional woman riding donkeys and horses. Animals were hauling carts with produce and goods. No sign of electrical wires and not much burnt brick. Just the dun of adobe structures with rough wooden doors and windows and the poles supporting the veranda roofs. (Shakes his head.) It was incredible.

Belica: I wonder what it is like now.

(Crook shrugs.) Crook: I don’t know. I can’t imagine what more than three decades of war in Afghanistan has done to Bamyan, aside from the desecration of the Buddhist relics. I read somewhere that the Soviet-Afghan War of 1987-88, at least, was fought mainly outside of the central region in which Bamyan is situated and left it relatively undamaged.

Belica: So, when did you get to Bamyan?

Crook: We didn’t get there until late in the afternoon. Then it was first things first. After taking a passing look at the magnificent Buddhas on the north side of the valley in the waning sunlight, we headed for the Bamyan Hotel. Someone at the conference had mentioned it to me as the only place to stay in Bamyan. It was perched on the edge of a low plateau on the south side of the valley and had a great view of the Buddhas to the north.

Mohammad Aref |

Belica: How was the hotel?

Crook: It was all right. It had its own generator, so I had electricity in the evening. Mohammad Aref had friends or kin in the village, so he stayed there. It was cold and there was no central heating, but my room had a fireplace and a fire in it was kindled by one of the staff. It warmed up the room and made it seem more cheery. The food wasn’t bad, but I’m no gourmet.

Belica: Did you visit the Buddhas the next day?

Crook: You would think that I would do that, but, no, for some reason I cannot recall, I decided to visit the nearby Band-e Amir first. When we started out, I saw two German girls in the backseat of the taxi. They were traveling on the cheap, as they say, and Mr. Aref had generously offered them transport in my exclusive taxi to the lakes where they were meeting up with friends. I didn’t bother to ask him how much he was getting for this little burst of private enterprise. They spoke halting English and were tanned from outdoor living on their trek to India, I think it was. At first, I was annoyed, but their appreciation of the magnificent scenery and anecdotes of their adventures made them welcome.

(Crook pauses and glances at Belica before continuing.)

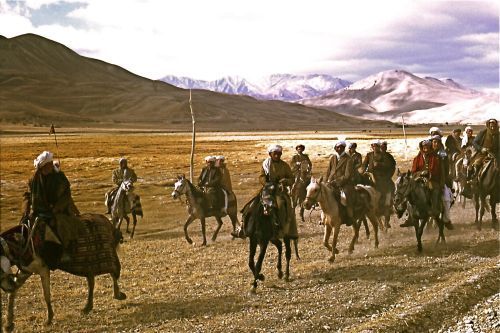

Crook: I can save some time if I just read a passage from my diary describing the trip: ‘The drive was beautiful and/or awesome—the rolling high hills and mountains of Central Asia. The landscape was on a vast scale. We passed a colorful Hazara wedding party on horseback riding to or coming back—I don’t know which—from the ceremony…’

Belica: Can you say something about the Hazaras?

Crook: Well, there are two main groups of Persian speakers in Afghanistan: the Tajiks who speak a dialect like that of the Iranian northeastern region called Khorasan. In Afghanistan, they are a majority in the northwest, which adjoins Khorasan. The Hazaras are mainly in the mountainous central region. Bamyan is more less their center. They form a kind of buffer between the Tajiks, the Uzbeks (who speak a Turkic language), and the Pashtuns to the south and east. The Hazaras also speak a Persian dialect and are Shiahs, like most Iranians, while the Tajiks are Sunni, as are the Pashtuns.

Belica: Whew! With all those different languages and the Sunni-Shiah division, I can see that national unity may be hard to achieve.

Crook: Yes, but the frequent invasions by outsiders has been a unifying factor, at least at the time of the invasions. In the 19th century, Britain invaded Afghanistan at least twice. The first was a disaster, ending in 1842 with the massacre of the retreating British army. Some sixteen thousand of their soldiers were lost!

Belica: That’s incredible!

Crook: Yes, it is, but it is the price of empire. That was the era of the ‘Great Game” as Kipling referred to it Kim: the game between the Russian Empire and the British Empire for domination in Central Asia.

Belica: What was driving it? Russia was the largest country on earth, stretching thousands of miles from central Europe across Asia to the Bering Sea.

Crook: Imperial ambition, what else? The most important possession of the British by far was the Indian Empire. The British considered its northwestern frontier its most vulnerable spot. They controlled the seas with the world’s largest navy and the Himalayas protected India’s north, but the Pathan region and Afghanistan were not so easily controlled.

Belica: And the Russians?

Bamyan Wedding Party |

Crook: Their huge empire was constricted by geography. As commerce by sea was replacing overland trade, they needed access to warm water ports. The ones they had were very vulnerable. The great Arctic Ocean to the north was icebound much of the year. Vladivostok in the Far East was on the Sea of Japan. The barrier of the Japanese Empire could easily render it useless in times of conflict. It was also thousands of miles from the Russian heartland.

Belica: Yes, I see. And that would be true of their ports in Europe. St. Petersburg is on the Gulf of Finland and ships would have to pass through the Baltic Sea before reaching open water.

Crook: Yes. And in the 19th century, the map of Europe was quite different from what is today. They had several other ports on the Baltic Sea then, but they would still have to pass through the Baltic before reaching the North Sea, which was still dominated by the British Navy.

Belica: And that would be true of the ports on the Black Sea as well. Ships would have to pass through the Turkish controlled straits of the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles, then 2,000 miles of the Mediterranean—

Crook: Which was controlled by the British navy at Malta and Gibraltar.

Belica: What has this to do with Afghanistan and the Great Game?

Crook: Throughout the 19th century, the Russians were absorbing bits and pieces of Central Asia until they reached Afghanistan, much as the British were doing in India until they reached its eastern borders. The British did not want the Russians so close to India. What did the Russians want?

(Belica thinks a moment. Suddenly, he looks up.)

Belica: Warm water. A warm water port on the open seas. They wanted to reach the Indian Ocean.

Crook: Yes! And the straightest route went through…?

Belica Afghanistan. And the British would have done anything to prevent that.

Crook: That was the essence of the Great Game. Afghanistan remained a tough barrier between the two expanding empires.

Belica: That was probably the Soviet motive for invading Afghanistan in 1989, reaching the Indian Ocean. So the Great Game really isn’t dead, is it?

(Crook shakes his head.)

Crook. Both empires backed off from direct confrontation and Afghanistan survived as a buffer state between the two great empires: the British and the Russian, later to become the Soviet Empire.

Crook: In any event, the Afghans got tired of being trampled on by the Brits, so the next time, they invaded British India and they fought the third Anglo-Afghan war in the early 20th century. They didn’t get very far, but they soon returned home with a treaty ending British control of their foreign affairs. The British had just fought the First World War and were getting a little tired of the price of empire.

Belica: It was about time.

Crook: Yes, it certainly was, but the British Empire survived until the middle of the 20th century. Anyway, after the Third Anglo-Afghan war, the Afghans were left alone for a while. Without a foreign enemy to unify them, the tribal, ethnic, and cultural differences inevitably resurfaced. There followed a dismal history of coups and assassinations for the next several decades as they struggled to find a formula for survival as a nation.

Belica: How was it during your visit?

Crook: At that time, fortunately, there was relative political stability with the long-reigning King Muhammad Zahir Shah still on his throne, but he lost it six years later when a cousin staged a coup d’état and declared a republic. Six years after that, in 1979, the Soviets once again eyed the route to the Indian Ocean, invaded Afghanistan, and began the war which re-unified the Afghans once again—or at least most of them,—against a common foreign enemy. It was then that the Americans entered the Afghan picture big time, albeit not officially, just subversion, sabotage, and the CIA. That war ended in 1989, a disaster for the Soviets and with hundreds of thousands of dead and maimed in Afghanistan. The Soviet Empire broke up soon after the debacle. That was followed by non-stop civil wars that lasted until the American invasion in 2001…

(Once again the patient, peace-loving parakeet pair erupt in noisy protest at all this talk of war.)

Crook (laughing): Do they really understand us?

Belica (also laughing and trying to hush the birds): They get upset when they hear arguments.

Crook: And war is the ultimate argument.

Belica (whispering): Perhaps we should get back to Bamyan.

Crook: Agreed. Where were we? Oh, yes, on the road to Band-e Amir. Umm, we spent about an hour and a half driving through this valley with a series of lakes, each a different color. It was quiet as only the country can be quiet except for the occasional vehicle or motorcycle. The German girls saw their friends near the little mosque on the shore of one of the lakes. They waved to them, gathered their backpacks, said goodbye and started down the slope to the lake.

That mosque, by the way, is associated with Hazrat Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, hence the name ‘Band-e Amir.’ It means in Persian, ‘The Dam of the Commander,’ a reference to Hazrat Ali in his role as Commander of the Faithful; that is, as the fourth caliph of the Islamic Commonwealth.

Belica: I never heard that Hazrat Ali visited Afghanistan.

Crook: It’s not in any of the standard authorities that I have consulted, but it is a widely accepted belief in Afghanistan. They say that he came there and, among other things, slew a dragon in the vicinity of Bamyan. The next day, after spending the morning at the Buddhas, Mohammad Aref took me to Azhdahah—that’s Persian for ‘dragon’—and told me the story as we drove:

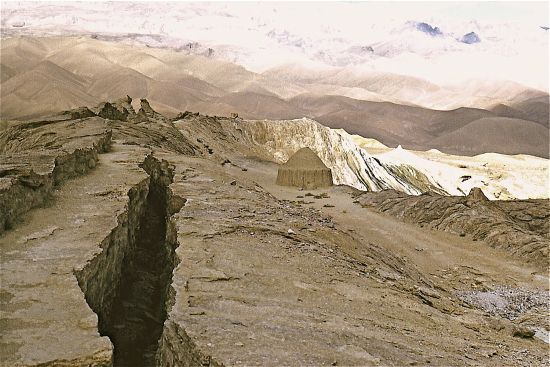

Petrified Dragon |

A dragon was terrorizing the region so much so that the people feared to go out of their houses to work their fields. When they tried to reason with the beast, he snorted fire and told them that if they wanted him to stop, they would have to supply him a beautiful young girl to eat every day. The people could not defeat the dragon, so they were forced to accede to its demands. Hazrat Ali heard of this horror and came to the place of the dragon and slew it with a sacred sword. The dragon instantly turned to stone and can be seen even to this day. Mohammad Aref assured me that the story was true.

Belica: His proof?

Crook: A weathered rock formation about 300 yards long that, with a little imagination, can be construed to be the petrified remains of a dragon. When we were examining it, he pointed to the cleft in the rock at the top that ran most of its length. ‘That was the dragon’s spine,’ he said triumphantly; proof that the beast had been cloven by the sword of Hazrat Ali. Of course, this is in the heartland of Hazara country and the Hazaras are Shiahs. ‘Shiah’ means ‘party’, that is, the party of Hazrat Ali. Whatever the truth may be, the petrified dragon is situated in magnificent mountainous terrain.

Belica: Do you have pictures of all these places?”

Crook (grinning): Need you ask?

Belica (also grinning): I think not.

(Becoming serious) Belica: You passed over your visit to the Buddhas. Wasn’t that supposed to be the high point of your Bamyan tour?

Crook: Yes. I was distracted by the memories of that ancient landscape with its forts, ruined cities, fortified family compounds with watchtowers still in use… so much to see and remember. And the people there; hardworking, but reserved. The Hazaras are often discriminated against in modern Afghanistan, as they were in past. They are not strangers to oppression, even in their homeland. It’s sad; amidst so much natural beauty…

(Seeing the expression on Belica’s face) Crook: The Great Buddhas, yes. You know, they truly constituted one of the wonders of the world, worthy of a journey by themselves. They were carved from the living rock, on a monumental scale. The Great Buddha was over 17 storeys high, while the Small Buddha was 12 storeys. When they were new, they would have gazed over the rich fields of the Bamyan, but they had both lost their faces a long time ago to other vandals. Staggering!

I spent a lot of time inspecting the ‘grottoes’ as they are sometimes called. They were the chambers carved around the Buddhas and connected by stairs and passages. I was lot more agile in those days than I am now, so I visited every accessible place and, I suppose, I tried to absorb the aura of the long-departed occupants of those rooms. They were used by the Buddhist monks and probably their visitors. They still retain bits and pieces of the original fresco-like artwork and have been cleaned of the soot from the fires that blackened much of their surfaces.

Belica: Do you think they were destroyed too when the Taliban blasted the statues?

Crook: I don’t know. Those grottoes close to the Buddhas were probably damaged if not destroyed. The ones farther away may have survived the artillery assault.

Belica (wistfully): I wish I could see them the way you did, I mean before.

Crook: I wish you could too. There is talk of restoration of the statues, but with the NATO occupation and ongoing unrest, I don’t think that will be feasible for a long time.

Belica: From what I read, I think you’re probably right. What did you do next?

Crook: The next day, we started out at 7:30 AM and after a couple of car problems solved ingeniously by Mohammad Aref with materials at hand—for example, the steering tie to the right front wheel broke, so it would only steer to the left; he replaced the tie with a strip of rubber—we arrived back in Kabul. I got a room in the Javid Hotel and bade Mr. Aref a fond farewell.

Belica: So, where did you go next?

Crook: The next day, I visited the Tomb of Timur Shah and walked about. Kabul was not a particularly friendly city, nor was it hostile. People usually just minded their own business—except for touts. The ones in Kabul are nothing like you encounter in Egypt around the big tourist spots. I liked it well enough, although I think Herat was much more sociable, but then that is a Persian city, and I was always at ease in Iranian towns. Kabul, though it is the capital and it naturally attracts people from all over Afghanistan on business or work, it is primarily a Pathan—or Pashtun, if you will—town and Pasthuns are generally a bit more reserved than Persian speakers.

Belica: And then?

Crook: I was still in Kabul so the next day I went by bus to Ghazni on a day trip. It was about 90 miles southwest of Kabul on an asphalt road. On the way, we had a flat. The driver searched but couldn’t find a jack! Solution? We all got out of the bus and lifted it up so that the driver and his helper could remove the wheel and change the tire. Once back in the bus and on our way, the group effort made us all more sociable even with the driver.

Belica: That must have been fun! Ghazni. I’ve heard of that. Something to do with Mahmud of Ghazni.

Crook: Yes. A thousand years ago, he created a great empire in the region. Though of Turkic origin, there are many stories about him and his contemporary, Ferdawsi, the Persian author of Iran’s greatest epic, The Shahnameh.

Belica: What does the title mean?

Crook: The Book of Kings. According to the story, Mahmud and Ferdawsi had a stormy relationship. Finally, after a prolonged separation, Mahmud relented and sent a rich present of gold to the poet. As the caravan carrying the gift entered the city—it was Tus, near modern Mashhad—it met the procession escorting the body of Ferdawsi to the cemetery. He had just died.

Belica: Sad. I wonder if it is true.

Crook (shrugging): I like to think it is. Anyway, Mahmud built Ghazni into a splendid city of palaces, mosques, and monuments. Today, virtually nothing of that remains save a couple of magnificent towers, and they were built a century after him. All the other marvels he constructed have vanished, obliterated by war, ending with the razing of the city by Genghis Khan. Sic transit gloria mundi! Thus passeth the glory of the world. All empires are ultimately defeated by time.

Belica (nodding): True. What was it the philosopher said: ‘Those who cannot learn from history are condemned to repeat it’?

Crook: Yes. Santayana. (Looks at his watch.) I see we are running short of time, so let me just say that the day after, I began my circular tour of Afghanistan. My plan was to travel by bus to Herat via a stop at Kandahar, fly from Herat to Mazar-e Sharif in the north as there was no highway yet between the two cities, and then after a few days there and a visit to nearby Balkh, I would return to Kabul before flying back to Tehran.

Belica: And you were able to do it?

Crook: Yes, all went according to plan. I got on a bus out of Kabul bound for Kandahar where I planned to stop a few days and explore. It was a Wednesday again, this time the 18th of October. As it happened, the man sitting in front of me was a gregarious middle-aged Iranian businessman on a buying trip to Afghanistan. We got chatting as the people often do in the Middle East when in such situations. When he found out I had learned Persian and was living in Tehran and working for the Peace Corps, we became instant friends. I guess we call it networking now. Anyway, he introduced himself as Ali Abrishami. Besides being a shrewd businessman, he was also a devout Shiah and we frequently discussed religion. The Shah was still on his throne, so we left politics alone. He was traveling with an Afghan merchant as well as several others. We all went to the Kandahar Hotel as a group of six and stayed together.

Belica: Did you tour Kandahar?

Crook: Oh, yes, we did. Mr. Abrishami and his colleagues spent a lot to time doing their business while I was free to roam. (Crook glances at his watch again.) After Kandahar, we went on to Herat as a group. I remember being a guest at the home of one of the Afghan merchants. It was a kind of smorgasbord, but instead of a big table loaded with different kinds of foods, we sat on a carpet in front of a dining cloth and there were about a dozen small bowls of different dishes—greens, lamb, chicken, rice, lentils, you name it—even fish, placed arounf each guest’s plate. It was fantastic!

Belica (smacking his lips): Why didn’t they invite me?

Crook (laughing): I don’t think you were born yet. We parted company there. Mr. Abrishami returned to Tehran via Mashhad and I flew on to Mazar-e Sharif and the reputed Tomb of Hazrat Ali there. You know, Zoroaster was born in nearby Balkh and I visited a defunct, as far as I could tell, old Zoroastrian fire temple there. I guess that’s enough travel for now.

Belica: And from there you went to Kabul.

Crook: Yes. I spent another five days there and returned to Tehran.

Belica: Before we end this conversation, do you have any other thoughts?

Crook: Well, looking back at the past half century, I can see that period —the sixties— was a bit of a fluke. It is a testament to those times of comparative peace that I was able to do so. There were mechanical failures in transportation, but I did not have to dodge bullets or drone attacks. Hundreds of young—and not so young—men and women were able to set out from the United States and Europe and travel across the Middle East, Afghanistan, and Pakistan to find nirvana in India, if they chose, or just for the excitement of seeing the world in a personal way, rather than by organized tour with its schedules and itineraries, not that such tours don’t have a place in travel. They are often quite good and convenient. (pauses) Too, I often think about the places I visited and the people I met and wonder how they have fared through these decades of war. Where is Mohammad Aref, the Kabul taxi driver, now? Is he even alive after the virtually non-stop disorder and death in Afghanistan? I hope he is; if not, God bless him. And then there is Bamyan.

Upward view of the Great Buddha |

Belica: What about Bamyan?

Crook: It is a great cultural loss; not just for Afghanistan, but for humanity as a whole.

Belica: And it was deliberate.

Crook: That appears to be the case and that makes it more egregious. It is a sin of commission done by the Taliban. You know that there are sins of commission and omission.

Belica: Yes, doing some wrong deliberately and not doing something that you should and could do.

Crook: Exactly. The destruction at Bamyan was a sin of commission but, as an example, the pillaging of the Iraqi National Museum—which I had toured with Iraqi friends in 1965 during a Baghdad dust storm—was a sin of omission. American troops were present in the area and knew what was going on as one of the greatest museum collections on earth, of enormous value to scholars, antiquarians, and the general public, was being systematically looted. For a day and a half they stood by and watched, ordered not to intervene. The blame lies not with the ‘grunts,’ but rather right up the chain of command all the way back to Washington. Finally, museum staff were able to return and guard the place against further looting; but that was a bit like locking the barn door after the horses have been stolen. It was still another four days before American troops were posted to protect what was left.

That was a sin of omission, just as egregious, if not more so, considering the nature of the perpetrators, than the destruction of the Great Buddhas, and we, the American Empire, committed that sin of omission. Both are indefensible.

Belica: Another casualty of war, not counting the hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians killed and wounded in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Crook: And elsewhere and in the future, if we do not learn that peaceful negotiations are far better than violence and bloodshed. Let us wage peace between nations, not WAR!

(An explosion of raucous clawing and screeching shakes the birdcage as the peacenik parakeets, hearing Crook’s strong articulation of the word ‘WAR’, voice their just indignation at this foolish, self-destructive behavior of mankind. Crook and Belica nod at each other knowingly and grin as they watch the outraged birds. Belica turns to calm them by saying softly, ‘PEACE… PEACE… PEACE…’)

|

Agron, Jamal, Benjamin, and Alexander |

Salem-News.com Writer/Author/Musician Agron Belica, faced many challenges growing up as a rootless street youth, situations so intense that they threatened to destroy him- that is until he rediscovered his Muslim roots a few years ago and turned his life around.

In 2008, Agron Belica published his research article The Revival of the Prophet Yahya, and has caused quite a stir in scholarly circles. In 2009, a new theory was born, The Crucifixion: Mistaken Identity? John the Baptist and Jesus the Christ.

With no formal advanced education, he offers new interpretations of certain key words in the Quran along with his challenging theories about the role of John the Baptist in the Crucifixion and has attracted the attention of well-known scholars in the field of comparative religion, such as Dr. Laleh Bakhtiar, the first American woman to translate the Quran into English, the noted university professor, Dr. Mahmoud Ayoub, and the author and translator, Dr. Jay R. Crook.

When it comes to comparative religion, Agron has the ability to go up against the most studied religious scholars and few come calling. They fear his logical interpretations based on historical record, and they should.

You can write to Agron at this address: agronbelica@gmail.com

|

|

|

Articles for February 13, 2013 | Articles for February 14, 2013 | Articles for February 15, 2013

Quick Links

DINING

Willamette UniversityGoudy Commons Cafe

Dine on the Queen

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

MUST SEE SALEM

Oregon Capitol ToursCapitol History Gateway

Willamette River Ride

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

Historic Home Tours:

Deepwood Museum

The Bush House

Gaiety Hollow Garden

AUCTIONS - APPRAISALS

Auction Masters & AppraisalsCONSTRUCTION SERVICES

Roofing and ContractingSheridan, Ore.

ONLINE SHOPPING

Special Occasion DressesAdvertise with Salem-News

Contact:AdSales@Salem-News.com

googlec507860f6901db00.html

Salem-News.com:

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

Tim King February 16, 2013 2:40 am (Pacific time)

I really enjoyed preparing this incredible photo piece Dr. Crook, it is so good that your camera preserved a time period in this war ravaged nation. I received a large set of photos from the late 1960's in Kabul and this inspires me to do more with them. I certainly appreciate that you share memories from your extremely fascinating life, you are a great inspiration to all of us.

Peter February 15, 2013 9:54 am (Pacific time)

Great post people

Anonymous February 14, 2013 4:50 pm (Pacific time)

Great piece, really enjoyed the words and photos, thanks.

[Return to Top]©2026 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.