Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Jul-29-2012 22:04

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

Special Feature: A Pecan Epithet

Kent Paterson for Salem-News.comA common bond across species, pecans apparently inspire both birds and humans to go the extra mile.

Courtesy: start.epcc.edu |

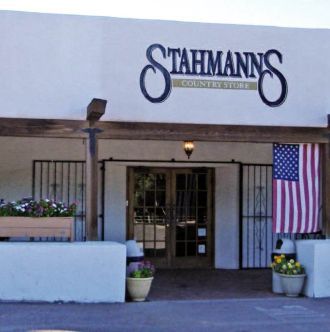

(LAS CRUCES, NM) - Observant travelers on New Mexico Highway 28 that passes through the immense, shady corridor of the Stahmann Farms pecan orchard in Dona Ana County will notice something is not the same. “Closed” signs now hang on the large white building off to the side of the road that was once the popular Stahmann’s Country Store, a place where shoppers could encounter not only a tasty bite of pecan candy but learn about southern New Mexico’s agricultural history as well.

Two months ago, the reality of the establishment’s pending closure was gnawing at Eva Valerio, then Stahmann’s Country Store manager.

“It’s starting to hit me. It’s an emotional roller coaster. It’s sad to see it go down,” Valerio told Frontera NorteSur, as the last customers strolled in on Memorial Day weekend to get a few final scoops of pecan ice cream or perhaps a bargain on the rapidly diminishing furnishings and office supplies for sale. “I’m going to miss a lot of the customers. We’ve built a lot of personal relationships,” Valerio said.

A second Stahmann’s store, on the historic Mesilla Plaza, was closed on May 6, Valerio said. According to the longtime New Mexican, 35 to 40 employees in the two outlets were impacted by the business decision, with a dozen or so quickly assigned new jobs within non-retail parts of Stahmann’s operation.

Opened for business in 1983 and specializing in company-made pecan candy and other treats, a stop at Stahmann Country Stores became a regular weekend getaway and holiday gift shopping tradition for generations of residents of the greater Paso del Norte borderland. Attracting visitors from Canada, Europe and South Africa-indeed the world over-Stahmann’s Country Store also gave outsiders impressions of the Land of Enchantment, its people, its economy and its identity.

Inside the once-buzzing premises, a video depicted the different stages of pecan harvesting and processing while photos of Mexican women working in the old candy plant provided glimpses of a rural society and a migratory history that lives on in the faces and language of the people of the Mesilla Valley.

Dr. Guillermina Nunez-Mchiri |

Dr. Guillermina Nunez-Mchiri, professor of anthropology at the University of Texas-El Paso, said the store’s shut-down marked a disconnect between the public face of farming and the public in general.

“The interaction between the customer and the producer is being erased,” Nunez-Mchiri said. Without places like Stahmann’s Country Stores, she added, the jaunts of city slickers into the countryside become less meaningful. “If those spaces aren’t there, people just drive and it becomes a passive interaction,” Nunez-Mchiri said. “There are trees but you don’t know the history behind those trees. And you don’t know the faces of the people working those trees and the history of the land.”

Valerio chalked up the store’s closure to reduced spending by corporate customers on employee extras, a drop in tourism, increasing overhead, and hard economic times brought on by the Great Recession.

“The economy still hasn’t gotten better, and there isn’t a lot of customers coming in,” Valerio said. “We don’t have enough business.” Stahmann’s found itself caught in a squeeze between declining business on the one hand and rising prices for fuel and products used in making pecan candy such as eggs and chocolate on the other, Valerio said. Attempts to curb costs, without raising prices, were unsuccessful, she lamented.

Stahmann’s Farm, however, will continue growing and wholesaling pecans, Valerio stressed.

Overall, New Mexico’s pecan industry remains solid amid the fluttering U.S. economy, due in good measure to steady export sales to China. In fact, the industry has now expanded north toward Albuquerque, with pecan trees lining several miles of Interstate 25 just outside Belen in Valencia County. Statewide, pecan acreage leaped from about 6,000 acres in 1960 to more than 37,000 by 2010, according to state and federal sources.

Courtesy: New Mexico State University |

The United States Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service reports that pecan production in New Mexico grew from 29 million pounds of nuts in 1985 to 66 million in 2010, soaring in value from just over $25.5 million to nearly $186.8 million in the same time frame. Best yet for producers, the price paid for each pound of nuts shot upward, increasing from 88 cents in 1985 to $2.83 in 2010.

Canopying the high desert, pecan trees have an old presence in the Southwest and northern Mexico. The Spanish name for pecans, “nuez pecanera,” refers to the tree from the Pecos Valley, said Dr. Enrique Lamadrid, an author and professor in the Spanish and Portuguese Department at the University of New Mexico.

In an interview with Frontera NorteSur, Lamadrid recounted how Spanish conquistadores stumbled across pecans and entire indigenous populations living off the trees. “They’re very nutritious, and you’re set to go,” Lamadrid said of the value of pecans to earlier civilizations. “You can base an economy upon them. In fact, a kind of pre-agricultural, hunting and gathering economy was built upon pecans.”

According to a report by the New Mexico Cooperative Extension Service, evidence indicates that pecan trees were brought to southern New Mexico from central Texas and north-central Mexico in the late 1800s or early 1900s. A four acre plot for cultivating improved varieties was planted at New Mexico A&M College, later New Mexico State University, in 1915 and 1916.

J.W. Newberry of Fairacres was an early Mesilla Valley pecan pioneer. By the mid-1930s, the Stahmanns were in the lead when they planted 30 acres of the stately trees at the old Snow Farm, thus beginning the expansion of orchards that now cover thousands of acres in Dona Ana County and the El Paso Valley to the southeast.

In the early years of the Southwestern commercial industry, pecans were decidedly not an item for the mass consumer market. Circa 1930, for instance, the New Mexico Extension Service report estimated that it took two hours of labor for an average worker to purchase a pound of pecans. Compare that toil to the early 1990s, when a minimum wage worker could buy three pounds of pecans with an hour’s worth of work.

According to Lamadrid, the New Mexico pecan business has a long historical connection with Mexico, especially in the Valle de Allende of Chihuahua state, where an “80-mile pecan forest” covers the land. As the New Mexican nut industry developed, “pecan scouts” from north of the border showed up in Chihuahua looking for suitable root stock, Lamadrid said. In the Valle de Allende, the trees are allowed to grow taller and even sport individual names, the UNM scholar added. A practiced visitor to Mexico’s land of pecans, Lamadrid recalled the fate of a friend’s tree that was monikered “Sixto.”

One day, the New Mexican was visiting Chihuahua and noticed the giant tree gone. “Where is Sixto? Que paso con Sixto?” Lamadrid wondered aloud, only to find out that Sixto had been zapped by lightning and burned. “But where Sixto had been a ring of young pecans just sprang up on the same spot,” he added.

Back home in Albuquerque, Lamadrid planted a tree that now towers 40-feet above his property. While large commercial operations like Stahmann Farms employ mechanical harvesters to gather the nuts for market, Lamadrid uses another harvesting method. He simply lets crows do the job for him.

“For every nut that they actually get and take out to the street and let the cars run over it to get at, they cause another five or six to drop down to the ground...,” he chuckled.

A common bond across species, pecans apparently inspire both birds and humans to go the extra mile.

Rose Marie Mendoza of Las Cruces and her daughter Angela Fabacher of New Orleans are among pecan lovers. For a long time, the family made regular stops at Stahmann’s Country Store on their way to another favorite Mesilla Valley landmark, Chope’s Bar and Café, just down Highway 28 in La Mesa. “I always stop to get pecans and candies to take back to New Orleans with us,” Fabacher said. “You grow up eating pecans from here.”

Asked what they would do without Stahmann’s famous pecan candies, the mother and daughter had different answers.

“Do without,” Mendoza shrugged.

“Learn to make them!” Fabacher vowed.

-Kent Paterson

Frontera NorteSur: on-line, U.S.-Mexico border news

Center for Latin American and Border Studies

New Mexico State University

Las Cruces, New Mexico

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Articles for July 28, 2012 | Articles for July 29, 2012 | Articles for July 30, 2012

Salem-News.com:

Quick Links

DINING

Willamette UniversityGoudy Commons Cafe

Dine on the Queen

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

MUST SEE SALEM

Oregon Capitol ToursCapitol History Gateway

Willamette River Ride

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

Historic Home Tours:

Deepwood Museum

The Bush House

Gaiety Hollow Garden

AUCTIONS - APPRAISALS

Auction Masters & AppraisalsCONSTRUCTION SERVICES

Roofing and ContractingSheridan, Ore.

ONLINE SHOPPING

Special Occasion DressesAdvertise with Salem-News

Contact:AdSales@Salem-News.com

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

[Return to Top]

©2026 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.