Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Jul-25-2011 19:07

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

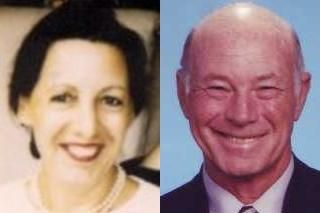

Silvia Cattori's Interview with U.S. Ambassador Samuel F. Hart

Salem-News.comAmbassador Hart has experience as a soldier, a diplomat and a teacher. He has degrees from the Univ. of Mississippi, the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, and Vanderbilt University.

Silvia Cattori and Samuel F. Hart |

(ROME) - Samuel F. Hart, 77 years old, retired US Ambassador, looks much younger than his age. With intense and calm blue eyes, discreet, friendly, he smiles warmly at you and tells you what every honest politician or well informed diplomat should be able to tell you, but does not usually. It was very surprising to meet in a modest three stars hotel in Athens this distinguished man who was waiting with three hundred others participants in the “Freedom Flotilla II” for the Greek government to let them leave for Gaza. We want to thank him warmly for having responded to our questions in a very respectful manner, without any restraint or hesitation.

Silvia Cattori: You arrived in Athens at the end of June, with the aim of going to Gaza. Ten days later, the Greek coast guard has so far given no sign that they will let the ships of the “Freedom Flotilla” leave the harbor. What is your feeling? Should the organizers continue to try until the inhumane and illegitimate blockade of Gaza is lifted?

Samuel F. Hart: [1] One can always hope that something good will happen. I am assuming, if that flotilla does not go, that there would be some similar effort. If so, I would try to do it differently— maybe by choosing a different country of departure; maybe by finding some different way to buy the boats. But I assume that people will not say: “OK, that’s that, no more”. I think they will try again. But who knows whether they will try one time more or ten. That depends so much on what else happens. To say “OK, the Israelis won” and to accept this as a final defeat would be unwise. I don’t think these people will say that.

Silvia Cattori: In the previous “Freedom Flotilla”, nine Turkish people were killed and many others were injured by Israelis soldiers in an Israeli raid on the Gaza-bound Turkish ship Mavi Marmara. The fact that the Israelis could do it again does not frighten you?

Samuel F. Hart: Look, I am an old man. What can they do to me? If I am able to do something, I must ask myself the questions: if not me who, if not now when? Those who are able have an obligation to stand up against the oppression of the weak. We have an obligation. We are all human together; and when you see people being oppressed and you can help them, it is your obligation to do so.

I chose to be here because I think the issue is important. And I am in a position to help.

Silvia Cattori: The fact that you are ready to put your life on risk in order to express your solidarity with the Palestinians is something very impressive. If you do not succeed, you can be proud to have tried, whatever happens...

Samuel F. Hart: There may not be so much danger. But, of course, I am ready to take that risk. You know, there are only a few things that are really worth doing. If you try to make the world a better place, you must try to contribute something to that better world. And if you fail, you still try. Trying and failing is better than not trying at all. All people involved in this can take pride in themselves for doing something for others. There are many ways to do something for the people. You can help your neighbour, you can help the sick, and you can donate money to the Red Cross. This is also a noble way. It has a certain special meaning because it involves putting your body at risk.

Silvia Cattori: Did you expect that the “Freedom flotilla II” would face so many problems from its start?

Samuel F. Hart: I won’t say that I expected it, but I am not surprised. I did not expect it to be totally without problems. However, I thought that we would make it out to sea and sail for Gaza. I thought about how I was going to behave when the moment of truth came with the Israelis. I did not think about how I was going to behave towards the Greek government, or towards the American government. So it is like you go to fight one war and you discover you are in a different one.

I don’t know what motivates the Greek government to be an ally of the Israeli government on this. Some people have suggested it’s because of Greece’s economic and financial problems. They speculate the Israelis have said: “If you want us to be helpful, you have got to do this for us”. I don’t think that the Israelis have that kind of power. But the United States of America does have it. I believe that the only way the Greek government would have been convinced to prohibit the sailing of the boats would have been if the Americans intervened.

What I am surprised by is the amount of fear that the Israelis have of this flotilla. It’s amazing the amount of energy and the political pressure they have exerted. I am surprised that they have gone as far to try to prevent the flotilla. If I were leading the Israeli government, there was a very simple way to deal with the flotilla, but it is totally contrary to the character of the Israeli government. The way for Israel to deal with it was to say: “OK, let the flotilla leave. We are going to board the ships and we are going to search the ships to determine that no arms or anything related to military equipment is on board. And then go on, go to Gaza, upload, we won’t interfere.” The international press would have praised the Israelis if they had said that, and it would have been a one day story.

But this kind of behaviour is beyond the capability of an Israeli government. Israeli authorities often believe that the other side only understands violence. Most Israelis believe that too: so, if your violence doesn’t work, as happened with the “Freedom flotilla I”, the next time you raise the level of violence. And this has happened time and time again.

Silvia Cattori: For Israel, all the “Freedom flotillas” are simply a provocation!

Samuel F. Hart: I come back to the civil rights movement in the United States. What happened there is similar to what is happening in Gaza. Many of us on the American delegation say: “We are here for the same reasons that freedom riders went to the south of the United States back in the early nineteen sixties. Because we see a wrong, we want to bring public attention to it. We don’t want the silence to continue. We want to initiate a public debate. Therefore, we are trying to find a way to cause people to take notice; not let them be comfortable and ignorant.”

Is this provocation? It depends on what you mean by provocation. It is a challenge; but I wouldn’t call it a provocation. To call it a provocation implies that the people in the flotilla are responsible if anything bad happens to them. That is blaming the victims. It is like if you offer me a bunch of flowers and I hit you in the head, you claim that you are guiltless because I should know you don’t like flowers. So, it was your fault that I hit you in the head. In Hebrew that’s called chutzpah. It is said that the definition of chutzpah is when someone who murdered his father and mother asks the Court for mercy because he is an orphan. I am terribly ashamed that my government seems to be adopting that attitude towards the flotilla.

Silvia Cattori: In case the “Freedom flotilla II” can not sail, after so many efforts, will it not cause a big frustration?

Samuel F. Hart: People come to this for many different reasons. If you are a Palestinian you are here because it’s about you; and if you are someone like myself, it’s because you see an injustice and want to see the injustice make right. So, if this is a failure, people will react in many different ways.

Silvia Cattori: A number of journalists and citizens are probably following that event in the United States. If, finally, the “Freedom flotilla II” cannot take to sea, what will you tell them when you are back home?

Samuel F. Hart: What I expected to do when I got home was to say: “I got on this boat. We set out for Gaza. When the Israeli navy came, they arrested us all. They kept us in jail for few days and finally they expelled us from Israel and said we can’t come back for ten years.” After telling that story I would add that because we got the world’s attention for just a few minutes about an issue which is ignored most of the time, whatever cost in terms of time and money was worth it.

That was what I was hoping would happen. Now I can’t do that, if we don’t go. If we don’t go, I have to say: “We wanted to go. We tried to go. We ran into problems that made that impossible because of the action of the American government and the Israeli government and the Greek government. We think our cause is just. We think that it is something that deserves the world’s attention. At least it got a few minutes in the international media. And we shall return.”

Silvia Cattori: Do you think that mistakes were made in the organization of this “Freedom flotilla”?

Samuel F. Hart: Since I don’t sit in the strategy meetings, all I can do is watch the shadows on the wall. You never see the real figures, you just see the shadows. I think the very nature of this organization and the people involved lead to a certain amount of disorganisation. If, for example, we had been able to get the flotilla going in May, it would have been easier. I am not saying that the American government and the Israeli government would not have found ways to make it difficult. But I think that the fact that it was delayed so long - from March, to May, to June, now in July - gave them a lot of time to find ways to make the flotilla, not impossible, but much more difficult.

You know, when you are dealing with twenty or so countries, and many organizations including some competing within countries, all of this reduces the strength, the solidarity of the movement and makes coming to agreements more difficult. But that is not to say that we would not have reached exactly the same result. I just learned today that there was sabotage on the boats a year ago. I did not know that; so one would think that you would try to find a way to keep that from happening. It easier said than done. Boats are in the water. You find a harbor and you don’t have control of the harbor security. So, it’s hard to keep sabotage from happening if somebody has ability to attack some of the boats using frog men.

It is really disappointing that, at this moment, we are not really of one mind. I am not here to throw stones at anybody. I am just one volunteer saying that I hoped that we could have found a way to confront the Israelis; the real aim. Not the American government, not the Greek government, not each other; but it’s hard to do.

Silvia Cattori: Have you something to suggest to the organisers of the “Freedom flotilla” that has to be improved?

Samuel F. Hart: I think that if you had a management consultant looking at this organisation, he would recommend hiring someone like a wedding planner or an event planner that is full time on the job. That person would collect all the information and draw up a schedule that says what we are going to do. So, all of the people involved must be ready to act quickly. Now, I know that when you have a volunteer organisation – I have belonged to a lot of them – it is hard to do. But without really good management at the top level, things just don’t work very well in general: too many voices, too many cooks.

Silvia Cattori: Today, July 4, the US Independence Day, as a former US ambassador you might be welcomed at the luxurious official party at the American Embassy. But you are here, in this three star hotel, one among hundreds of participants who are motivated by the project to break the siege of Gaza. It is not something usual for a person at your official level, for an ambassador! Do you think that people in the United States can understand and support this commitment of one of their former representatives?

Samuel F. Hart: I don’t care about celebrating at the US Embassy. I remember the first Fourth of July speech I gave as an ambassador. It was during the Reagan administration. I said that when we celebrate the Constitution and independence, we sometimes also talk about patriotism. To some people patriotism means: “my country right or wrong”; whatever my country does, I support it. But that to me is not patriotism. To me true patriotism is not “my country right or wrong”. It is to help make it a more perfect union. It is to support the policies you believe are right and to try to change the policies you believe are wrong. I think that’s what true patriotism is all about. Now I would say that the great majority of people in the United States would disagree with that.

Silvia Cattori: Would they disagree and blame you? Would they consider that you are at a wrong place, a kind of traitor to the policy of your country?

Samuel F. Hart: The fact that at one point I served as an ambassador does not take away my rights as a citizen. It made it impossible for me to be openly critical on the US government policies when I was in that position. But today I can do whatever I want. I have no limits on my opinions.

I like to believe that you are allowed in the United States to disagree with the government policies without being labelled a traitor. Nevertheless, some people will look at it that way.

I opposed the Iraqi war too. After the first year or so when the Vietnam War came along, I was in Indonesia and Malaysia, right there near where it was going on. At first I thought we didn’t really have a choice but to pursue that war. Because at that time, the domino theory was conventional wisdom: if Vietnam goes, next goes Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and Indonesia. When I came back to the United States in 1964 and saw the price that the American public was paying for Vietnam, I changed my mind and opposed the war because it was a war that could not be won, or could be won only at a price Americans were unwilling to pay. No great national interest was at risk. I said it’s time to get out and I moved from being in favour of the war to being opposed to the war.

I was always opposed to the war in Iraq, because it was so stupid.

Silvia Cattori: To which political party do you belong?

Samuel F. Hart: I have always considered myself an independent. But at some point in my life I voted for liberal Republicans. Then the liberal branch of the Republican Party died. I am a progressive in the way that many liberal Republicans were. I am a fiscal conservative and a social liberal. Today, I vote mostly for Democrats.

Silvia Cattori: Is it not unusual to see an Ambassador so deeply committed? I could hardly find such an example in my country…

Samuel F. Hart: No, in United States there are many. I live in Jacksonville, Florida. That’s a long way from Washington DC. But I get messages every day from people who are in Washington. I think that if you privately asked every career diplomat who has served as an American ambassador, most of them would agree with what I have to say on the question of Israeli policy. Because few think that it makes any sense. It’s contrary to the American national interests. In many embassies, diplomats have an input in making policy. But in Israel, our diplomats have no voice in policy; never have had any voice in policy. That stuff is made in the White House and the Congress. Since that is something an individual can’t do anything about, you come to the point where you ask yourself whether your disagreement with policy is so important that you must resign in protest. Well, practically nobody does resign. After you have made your views known within channels, if you want to continue being a diplomat, you simply stay away from the areas of profound disagreement and find something else worth doing.

Silvia Cattori: When did you start to feel concerned about the oppression of the Palestinians?

Samuel F. Hart: In the years 1977 to 1980, I was stationed in the American embassy in Tel Aviv. At that time I was the economic and commercial counsellor; the number three person in the Embassy. I knew the West Bank and Gaza Strip very well. I spent a lot of time there and talked to the people. I saw what happened at that time. I saw the role of my government in not causing what happened, but in allowing it to happen. We did not say to the Israelis: No, you may not colonize the West Bank; no, you may not collectively punish the people in Gaza. At that time the focus was not so much Gaza. It was the West Bank. The West Bank was what really interested the Israelis. For historical reasons, Gaza was never part of Greater Israel. Gaza was always a foreign territory to Israel.

You remember the story of Samson in the Bible. Delilah was a foreigner, a Philistine from Gaza. That was not part of Israel. But the West Bank, which the Israelis call Judea and Samaria, was a part of an Israeli state at one point. What interests Israel in the Palestinian territories is really the West Bank. Gaza is a secondary thing. Because Gaza is Palestinian, it is involved in the larger problem. But if you said to the Israelis today: look, you can take all the West Bank and forget Gaza, they would take the deal in a minute.

When I was in Israel, I came to realize that the long term intent of the Israelis was to absorb all of the West Bank. The ideological framework of the Likud party, with Menahem Begin then at the head, and of the successor governments of the Likud party since then, has always been to expand Israel borders from the Jordan to the Mediterranean. The 1965 War made that a real possibility.

Silvia Cattori: Did you meet Benjamin Netanyahu?

Samuel F. Hart: No. When I was in Israel Netanyahu was a young man coming up the ladder. And he was very valuable to the Israelis. He went to the United States as a boy and went to school in the United States. I don’t remember what the exact circumstances were, but he lived in the United States as a teenager at least. And so, because he speaks fluent American English, he is very effective in talking to Americans. Since he speaks American English, we don’t say: Ah, he is a foreigner, like you might with someone who has a normal Israeli accent. He can say the most outrageous and the most destructive things in a very quiet and familiar way, and his charm makes it sound reasonable. It is a very big asset. But Netanyahu was not in power at that time. It was Begin and Shamir.

Silvia Cattori: When you met them what was your feeling?

Samuel F. Hart: I saw Begin on many occasions. Only once did I negotiate with him about something, because ordinarily the Ambassador did that. But once I was Chargé. The Embassy is in Tel Aviv and, of course, the Israeli government and everything except the Ministry of Defence is in Jerusalem. The Ministry of Defence is in Tel Aviv. One day Begin’s office called and said he wanted to talk to me I, of course, agreed. I then called Washington to inform them that I had been called to Jerusalem to see the Prime Minister. I said I did not know what the subject was, but asked whether there was anything Washington wanted me to raise with him? I went there and both Moshe Dayan and Ezer Weismann were present. I joked to them that I should have brought some reinforcement with me. I didn’t know I was going to see the Foreign Minister, the Minister of Defence and the Prime Minister all at once. What can I do for you, I asked? They had a request, and I said: Well, I will see, I will pass it back to Washington and I will get back to you the answer. And by the way while I am here is there something you can do for my country. It turned out that a mutually beneficial deal was struck. Anyway, I got to know Begin pretty well. But mostly I dealt on the economic side with the Minister of Economics, the Minister of Transportation and the head of the Central Bank. I never talked much with Shamir.

This was a time, 1977-80, when there was some progress made on peace. It was Jimmy Carter’s presidency, the time of the Camp David Accords and the Peace Treaty with Egypt. The treaty was a great benefit to Israel because Egypt was removed as the only credible military force facing Israel. In return, Egypt got back the Sinai Peninsula. But the only commitment that Jimmy Carter was able to get from Menahem Begin about the Palestinian problem was that there could be some talks with Palestinian “notables” about the future of the West Bank and Gaza. The PLO was excluded because at that time the PLO was still considered a terrorist organisation by Israel. Anyone who spoke to Yasser Arafat was guilty of a major crime. There was an Israeli who had a boat called The Voice of Peace. His name was Abie Nathan. He had a small ship with radio broadcasting equipment off the coasts of Israel. Abie went to see Arafat, maybe it was in Morocco, and he was charged with supporting the enemy. That was what happened to anybody who would speak to, or have any contact with, the PLO, that “terrorist organisation”. Does it sound familiar to you today?

Silvia Cattori: Most of the people, at that time, did not understand what Israel was. But, the people we know today, Netanyahu, Sharon, we have come to know how they act. Were the people you met at that time of the same style, as brutal, as cruel?

Samuel F. Hart: A little history about Begin. His entire focus was to make sure that something like the Holocaust never happened again. That was not only Begin; that was something that runs through the entire psychology of the people of Israel. And you can understand to some degree why. But when the debate comes to Netanyahu or Sharon, the question becomes what means do you use to achieve your ends? Begin was head of the Irgun, which captured two British soldiers during the mandate period, executed them and hung them upside down and booby trapped their bodies as reprisals against the British for having captured Irgun people. So he had bloody hands. Shamir was the head of the Stern Gang, which blew up the King David Hotel. Sharon has always been a soldier. And his attitude towards enemies was: we take no prisoners, we show no mercy. He was not a bad soldier to have on your side, but no one would ever call him a humanitarian. For all of these men, an Israeli innocent life was always worth the lives of many, perhaps an infinite number, of innocent non-Israelis.

Has it always been that way? No. In fact before that, before the rise of the Likud to power, there were people who were in the government, like Moshe Sharett, who had a different view. They were prepared to accept Israel’s borders as they were, and to try to develop a positive relationship with its neighbours; to be a peaceful member of the Middle East. For other reasons, that didn’t happen. The Arabs at that time were not prepared for that. They were still trying to reverse the results of the 1947-48 war. They still thought that they could defeat Israel. So they were not good partners for peace. But after Sharett, more and more and more of the Israeli political establishment accepted what was essentially Ben Gurion’s and certainly Begin’s view of the world; Israel is surrounded by enemies, we are constantly under threat of annihilation, therefore anything that we do to preserve our existence is justified. Therefore the end justifies the means. Therefore, we are not bound by the rules like the Geneva Conventions or UN Security Council resolutions.

Israel began escalating violence partly in response to small scale attacks on it. But once you get into a cycle of violence, you never know who started it. It was not a holy war because it is not about religion – but the downfall spiral of violence was going strong at the time of the Egyptian Peace Treaty. Egypt got something, Israel got a lot, and the Palestinians got nothing. I was the American representative at the talks after Camp David with the so-called “notable” Palestinians, who were allowed to come and talk with the Israelis. We had two meetings. At the first meeting it was very clear that the Israelis were not prepared to do anything. They wanted a Peace Treaty with Egypt and so they agreed to hold some talks, but they were from the beginning supposed to fail. And after the second meeting that was the end.

Silvia Cattori: Did you understand at that time that the Israelis would never give back any piece of land to the Palestinians?

Samuel F. Hart: I do not say that. I say the Netanyahu government would never give it back. There was a moment when this came close to happening. When Yitzhak Rabin was Prime Minister and he negotiated in good faith with the PLO, the Oslo Accords came along. Because Rabin had so much credibility with the Israeli public - he was known as Mister Security - he decided that he was ready to make peace and to give up the land. He was ready to do that and people from the Netanyahu school of thought killed him. Just like Muslim Brotherhood people killed Sadat. That is the reward you get for being a pragmatist and a peace maker in that neighbourhood.

Silvia Cattori: The rejection of injustice is not usually what guides the authorities of the United States; a country that conducts devastating wars that have caused since the fifties millions of dead and destroyed entire countries. It is not common here in Europe to see an ambassador join in all humility to the action of private citizens who call international bodies to stop covering the crimes of Israel. What is your background?

Samuel F. Hart: I joined the foreign services partly because I thought that I could do something good; in some way make the world a better place. Going forward, what bothers me so much is not that the Israelis do what they do, but that my government and my taxes help them do it. And that it is the reason why I feel that, as a man who knows enough about this situation to be able to speak with some authority, I have an obligation to do it. That’s why I am here.

Silvia Cattori: When did it become clear for you that your government was going on fighting and making illegal war against many countries; that something was wrong in the US foreign policy?

Samuel F. Hart: Before I was in Israel I never focused on the Israelis. When I was there, there were quite a few Americans not of Jew ethnicity in the American Embassy. There were many people who were Jews. And the surest way of convincing an American Jew that Israel is not always right and does not always deserve US support is to send him to the American Embassy in Tel Aviv; because you see there everyday the duplicity, the meanness, the division of the world into them and us. And you might think that there would be some reciprocity, some kind of appreciation from Israelis who daily receive part of what they eat and what they use to enjoy life from the American tax payers. You would think that there would be a little bit more sensitivity to what United States feel is in its interest. And you saw that it is not true.

Why then does this continue? Here you get into the American domestic politics. As I frequently have said, if you want to find three subjects in the US that are clearly foreign policy issues but cannot be treated as foreign policy issues, one of them is the policy towards Cuba, one is drug policy; and the other is Israeli policy. These are all domestic political issues which are driven in parallel, not by the foreign policy interests of the US but by domestic political considerations of the president and the members of Congress. And this is true both for the Republicans and for the Democrats. And it is not going to change.

Silvia Cattori: But it is difficult outside to understand why the government of the United States leave Tel Aviv to do whatever it wants and even to answer them in a very arrogant way.

Samuel F. Hart: I asked this question once to a member of the US Congress who was visiting Israel. I said to him: tell me why each year when we get the Israeli aid request and I reviewed each line and write a report (and I know more about this subject maybe than anybody else) usually recommend some reductions. But when it gets to Washington you keep the amount the same or increase it. Why is that? And he said, if you do not understand that, you do not understand the American political system. If you are a member of Congress or a President or any elected official and you want to be re-elected, you look at the people who will work for you and the people who are going to work against you.

Silvia Cattori: Money, money...

Samuel F. Hart: It is not just money. And it is not only the Jewish part of the American lobby for Israel. It’s probable in terms of numbers that the Evangelical protestant part of the Israeli lobby is bigger— the fundamentalist churches. It makes it a very funny partnership. But they come in and they say to someone in the Congress: if you will vote with us on issues related to Israel, if you will be the supporter of Israel, we will support you with money, with turning out voters, and with positive views. On most issues there is another side, but on the Israel issue there is no other side. The Palestinians have no credible voice. The politicians go with the Israelis because if you do not - and there have been some people who did not - they will work as hard as they can to defeat you. And they are often successful.

Interview made in Athens on 5 July, 2011

Footnotes:

[1] Ambassador Samuel Hart has experience as a soldier, a diplomat and a teacher. He has degrees from the University of Mississippi, the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, and Vanderbilt University. He also attended the JFK School of Government at Harvard. His military experience included duty as a paratrooper and as a general’s aide. He was discharged as a captain. For 27 years Sam Hart was a professional diplomat with the US Department of State. His overseas postings were predominantly in Latin America (Chile, Uruguay, Costa Rica, and Ecuador), but also included the Middle East (Israel) and Asia (Indonesia and Malaysia). From 1980-82 he was in Washington as director of US relations with Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia. During his career with the State Department, Sam Hart received numerous awards for outstanding service. This led to his appointment as ambassador to Ecuador in 1982. Since retirement from State, Sam has been a business consultant and a lecturer on foreign policy issues at numerous colleges and universities as a Woodrow Wilson Visiting Fellow. For the past 15 years, he has also been a top-rated lecturer on cruise ships, speaking principally about US foreign policy. In 1994, Sam and his wife, Jo Ann, moved to Jacksonville, Florida, where they have both been active in the World Affairs Council and other volunteer activities.

P.S. On the Freedom Flotilla, see also:

“Huseyin Oruç: Whenever the Palestinians need it, the Mavi Marmara will go”, by Silvia Cattori, 21 July, 2011.

“There are too many headwinds to take to sea but the struggle continues”, by Silvia Cattori, 5 July, 2011.

Our special thanks to: Silvia Cattori for making this article available for Salem-News.com readers.

|

|

Articles for July 24, 2011 | Articles for July 25, 2011 | Articles for July 26, 2011

Quick Links

DINING

Willamette UniversityGoudy Commons Cafe

Dine on the Queen

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

MUST SEE SALEM

Oregon Capitol ToursCapitol History Gateway

Willamette River Ride

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

Historic Home Tours:

Deepwood Museum

The Bush House

Gaiety Hollow Garden

AUCTIONS - APPRAISALS

Auction Masters & AppraisalsCONSTRUCTION SERVICES

Roofing and ContractingSheridan, Ore.

ONLINE SHOPPING

Special Occasion DressesAdvertise with Salem-News

Contact:AdSales@Salem-News.com

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

Orwell August 2, 2011 12:59 pm (Pacific time)

This is to show my respect to Mr Samuel Hart, a graduate of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy who seeks order of law and justice in the world. Best wishes from Tokyo Japan.

[Return to Top]©2026 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.