Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Dec-16-2013 02:42

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

Bengal Under English Rule - an Analysis

Dr. Habib Siddiqui Special to Salem-News.comWHEN Bengal was colonised by the East India Company in the second half of the 18th century, it was the richest jewel on the British crown.

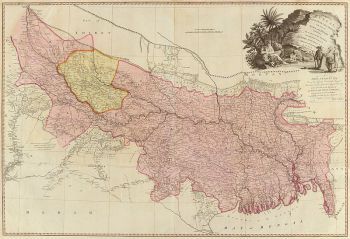

A map of Bengal, Bahar, Oude & Allahabad - James Rennell - William Faden. Wikimedia Commons |

(PHILADELPHIA BDNews) - As a matter of fact, the inhabitants of Bengal had a much better standard of living compared to most Europeans living at the time. But under the British rule, the tax burden became simply unbearable rising fivefold (from 10 per cent to 50 per cent of the value of the agricultural product) within a very short period of time. The agriculture sector was ruined by a faulty system, which encouraged cotton, opium poppy and indigo production over rice cultivation...

WHEN Bengal was colonised by the East India Company in the second half of the 18th century, it was the richest jewel on the British crown. Bengal by then had been under Muslim rule for nearly six centuries. During this long period from 1203 to 1757, as the rulers of the territory of Bangala (Bengal), Muslims held the administrative positions.

And yet, when the territory was divided in 1905, less than 150 years of English colonisation, into East Bengal, which was to later become the province of East Pakistan in 1947 and subsequently the independent People’s Republic of Bangladesh in 1971, and West Bengal, which was to later become a state within the Republic of India, the Muslims of Bengal lagged behind their Hindu counterparts economically and politically. Why?

To understand the causes, it is necessary that we have a fairly good grasp of the political, economic and social landscape of the territory, at least dating back to the time of the fall of the last independent nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-Dowla, in 1757.

The Hindu ascendancy in Bengal was not entirely a British phenomenon. As a matter of fact, a section of Hindu community had prospered beyond measures during the Muslim, i.e. pre-1757 English, rule of Bengal.

Many of them held important positions as ministers and generals during the Sultanate period of Ilyas Shah, before the Mughals came in the political scene of India [Dr Abdul Karim, Banglar Etihash, tr. History of Bengal: the Sultani Period, Dhaka (1998), p 413]. Many Hindus became very rich through such positions and others through money lending to actually become the bankers (like the Rothschild family of our time) to the nawab, and regrettably played the devious role which facilitated the downfall of the nawabi rule.

During the Mughal period, Bengal existed mostly as one of its outlying provinces or diwans and was locally administered by a subedar (provincial governor), who acted as the representative of the emperor. The subedar was responsible for collecting taxes and revenues from subjects, a portion of which had to be sent to the emperor and the remainder kept for meeting expenses for welfare of the province.

He also maintained a standing army and police force to protect the territory against any potential attack from outside and preserve law and order. Land tax collection (usually a fifth of the agricultural produce) was done through the zamindars [ibid, p 411) [In rare cases, e.g., in Benapole and Ghoraghat, feudal lords existed who instead of collecting taxes from the peasants paid an agreed upon sum of money as tax to the Muslim sultan to show his subservience to the higher authority [ibid, p 418].

In Bengal, which was a Muslim majority territory, most of the zamindars were Muslims during the greater part of Sultani and Mughal rule (until 1717). But things started changing drastically from 1717 onward when Murshid Kuli Khan became the subedar of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa (today’s Odissa and Jharkhand states of India). He held the position for ten years until 1727.

During his rule, the izaradar system emerged in which instead of the zamindars this new group became tax and revenue collectors [Jadunath Sarkar, History of Bengal, 2nd vol., Dacca, 1948, p 409]. Within just two to three generations they were able to replace the zamindars and came to be known as not only zamindars but also in places as rajas and maharajas.

All the chosen Izaradars during Murshid Kuli Khan’s tenure were Hindus. He did this in order to avoid competition from fellow Muslim nobles who might vie for his high position. Before him, as noted by renowned historians in their vast works, all the top administrative positions were held by Muslims, especially from the Uttar Pradesh [Salimullah, Tarikh-e-Bangalah, pp 403-4, 454].

The latter nawabs of Bengal simply followed the precedence of keeping Hindu izaradars, established by Murshid Kuli Khan. By 1757, when Nawab Siraj-ud-Dowla became the ruler of Bengal, these Hindu administrators had become strong enough to conspire and bring about his downfall. But there were some exceptions, as much as some of the Muslim nobles betrayed the nawab during the fateful Battle of Plassey (1757) and sided with the forces of the East India Company that was led by Robert Clive.

One such betrayer, Mir Jafar, who came to be known as Lord Clive’s donkey, became the next nawab and his reign lasted only three years (1757-60).

In a revolving door politics, he was replaced by Mir Kasim who tried to go against the wishes of the East India Company. He, too, was dethroned in 1763, and Mir Jafar was put back to power for the second time. After his death in 1765, his inept son Najm-ud-Dowla (1765-66) and younger brother Saif-ud-Dowla (1766), followed by son Mubarak-ud-Dowla ruled in succession.

By 1765, after the victory at the Battle of Buxar, the East India Company had won the diwani (representation) from the Mughal emperor, becoming the virtual ruler of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa.

Those nawabs since the fall of Siraj-ud-Dowla were merely titleholders by name only, and nothing else, for which they earned a pension out of the share of the collected revenue.

During Robert Clive’s dual rule, until 1774, the task of revenue collection was still at the hands of the puppet nawabs who collected the same through their Hindu representatives – the nayeb-diwans (tax collectors/izaradars).

His East India Company did not have the wherewithal to collect such taxes through its English employees and thus relied upon already existing system.

As to the share of the collected taxes, here is a breakdown: the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II in Delhi earned 2.6 million takas, the nawab of Bengal 3.2 million takas and the East India Company the rest of the collected revenue [Anisuzzaman, Muslim Manosh o Bangla Shahitya (tr. Muslim Mindset and Bengali Literature), 1757-1918, Dhaka, 1964, p 6]. [Note: Before Sultan Bahadur Shah Jafar was dethroned in the aftermath of the Sepoy Mutiny, he used to get a pension of 100,000 takas per month.

Similar to Bengal, although the official date for downfall of the Mughal empire is noted as 1857, the actual fall happened much earlier on September 14, 1803, when General Lake of the East India Company moved into Delhi with his British troops after capturing Aligarh. Since then Mughal rulers were drawing pension money from the East India Company [Jaswant Singh, Jinnah: India, Partition and Independence]. Under the East India Company administration, taxes multiplied exponentially and consequently, people suffered miserably.

Muslim peasants (i.e. the rayats) who were at the bottom of the economic pyramid were the worst sufferers in this revenue collection system. It is worthwhile sharing here a letter from Lord Clive, dated September 30, 1765, published in the Court of Directors of the East India Company. He wrote: ‘The source of tyranny and suppression opened by the European agents acting under the authority of the Company’s servants and the numberless black agents and sub-agents acting also under them, will, I fear, be a lasting reproach to the English name in this country.’ [Romesh Dutt, The Economic History of India under early British Rule, 3rd Edition, London (1908), p 37.] As already hinted, those so-called black agents were local Hindu tax collectors.

It should be also noted here that before the Battle of Plassey, Bengal was a very rich, prosperous province with enough for everyone to live a very decent life. As a matter of fact, the inhabitants of Bengal had a much better standard of living compared to most Europeans living at the time.

But under the British rule, the tax burden became simply unbearable rising fivefold (from 10 per cent to 50 per cent of the value of the agricultural product) within a very short period of time. The agriculture sector was ruined by a faulty system, which encouraged cotton, opium poppy and indigo production over rice cultivation. Moreover, the East India Company cared only about tax/revenue collection and nothing else. They did not do anything to improve the irrigation system.

To make things worse, the East India Company imported products enjoyed duty-free entry into the local market while the reverse was not true for local made products, e.g. muslin, into the European market.

The entire internal and external trade was monopolised by the East India Company. The weavers were forced to weave cotton yarns beyond their capacity.

Even under such savage, brutal, inhuman and ruthless work environment and tiring and back-breaking workdays, they would be paid so little that they could ill-afford having a full meal at the end of the day. Hunger and starvation was their lot.

Many cut their own thumbs to avoid being put to this kind of forced labour, others sold everything including even their children to escape being punished by the revenue collectors, and many fled the country [ibid, pp 23-27].

In 1769 the directors of the East India Company issued new directives stipulating that the peasants should be forced to produce raw material and not finished cotton or silk (resham in Bangla) products, and that such activities could only be done in company owned properties (and not at farmer’s cottage) [ibid, p 45].

Due to unfair trade practices, soon the entire cotton, muslin and silk industry got ruined. With one-way of flow of money out to Great Britain, while nothing spent for the good of the farmers and the local people, it was only a question of time when a great famine would ravage the country.

That ominous event came in 1770 when a third of the population, nearly ten million people, starved to death what has been called the Great Famine of Bengal even though that year the East India Company had the highest collection of revenue ever from the land [ibid, pp 52-53].

The East India Company also came up with a new system for revenue collection. It is called the ‘Sunset Law’ in which if either a revenue collector (i.e. zamindar) or a rayat (land holder) failed to pay the previously decreed revenue by a certain sunset time, his territory would be auctioned off to the highest bidder.

Almost all of these bidders were Hindu administrative officials, previously employed by Muslim zamindars. Many of them deliberately faulted upon payment on behalf of the Muslim zamindar so that later he could bid for the same territory using zamindar’s money.

Many of the new zamindars were Hindu officials employed within the East India Company’s government. These bureaucrats were ideally placed to bid for lands that they knew to be under-assessed and thereby profitable. In addition, their position allowed them to quickly acquire wealth through corruption and bribery. They could also manipulate the system to possess the land that they targeted. So by 1790 all on a sudden most of the zamindars or revenue collectors happen to come from the Hindu community who were mostly absentee landlords that managed their newly acquired zamindary through local managers.

Those new zamindars virtually became the oppressive hands of the East India Company imposing heavy taxes on the peasants. The situation of Muslims simply worsened after the Permanent Settlement Act, concluded by Lord Cornwallis in 1793, was enacted. Not only did the Muslim nobility, including the zamindars lost their properties, even the well-off farmers started losing their farmland as a result of company policy of high taxes, high usury rates charged by Hindu mahajons (moneylenders) and oppression of the new Hindu zamindars.

The East India Company’s policy virtually ruined not only the agricultural sector in Bengal but destroyed its rural cottage industry. Consider, for example, the case of muslin, the finest fabric ever woven in the world, which weighed less than 10 grams per square yard. Till 1813, Dhaka muslin continued to sell in London with 75 per cent profit and was cheaper than local British fabrics. Alarmed at this competition, the British imposed 80 per cent duty on the imported Bengali product. But more than the duty, the East India Company was bent on ruining the muslin trade by introducing machine-made yarn, which was introduced in Dhaka by 1817 at one-fourth the price of the Dhaka yarn. The Muslin weavers were also paid so little that their families remained hungry.

Another unsavoury fact associated with the destruction of this Dhaka Muslin industry was that the thumbs and index fingers of many yarn makers were chopped off by the British in order to prevent them from twisting the finer yarns required for the muslins, which would reduce the competitive edge that Muslin had enjoyed thus far over its counterpart fabrics made in Europe. While the machine generated British yarn was uniform in quality, something which could no longer be maintained by skilled weavers under inhuman company policy and practices, in 1840, Dr Taylor, a British textile expert, admitted: ‘Even in the present day, notwithstanding the great perfection which the mills have attained, the Dhaka fabrics are unrivalled in transparency, beauty and delicacy of texture.’ The count for the best variety of Dhaka muslin was 1800 threads per inch, while the lesser varieties had about 1,400 threads per inch.

To be continued

Dr Habib Siddiqui, a peace and rights activist, writes from Pennsylvania

http://www.bdnews21.com/

|

|

|

Articles for December 16, 2013 | Articles for December 17, 2013

Quick Links

DINING

Willamette UniversityGoudy Commons Cafe

Dine on the Queen

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

MUST SEE SALEM

Oregon Capitol ToursCapitol History Gateway

Willamette River Ride

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

Historic Home Tours:

Deepwood Museum

The Bush House

Gaiety Hollow Garden

AUCTIONS - APPRAISALS

Auction Masters & AppraisalsCONSTRUCTION SERVICES

Roofing and ContractingSheridan, Ore.

ONLINE SHOPPING

Special Occasion DressesAdvertise with Salem-News

Contact:AdSales@Salem-News.com

googlec507860f6901db00.html

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

GOGANTOR December 19, 2013 9:15 pm (Pacific time)

BANGLA

Hamidul Haque December 16, 2013 3:51 pm (Pacific time)

Please cover the latest socio-political events of Bangladesh and possible out come there after.

[Return to Top]©2026 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.