Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

May-02-2012 14:58

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

The Journey To Newcastle

Bill Annett Salem-News.comF. Scott Fitzgerald: Ernest,the rich are much different from us.

Ernest Hemingway: Yes, I know. They have more money...

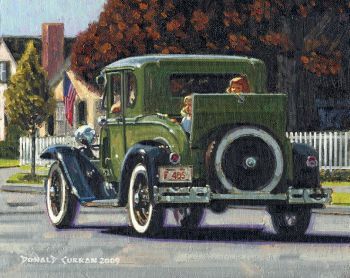

Courtesy: donaldcurran.blogspot.com |

(SASKATCHEWAN) - The summer of 1938 was an incredible journey, perhaps the first of the many discoveries that were to follow. But then, I was 10 years old and waiting only to see and understand. My vision then may have been clearer than I thought it would be later, until I reached the faltering clarity that comes with age.

My Mother's sister Grace lived a universe away in a place called Newcastle, in Wyoming. There were muffled exchanges between my Mom and Dad. My Aunt, we came to understand, was very old. Perhaps 45. As she lay dying. We could only go to see her one last time.

I've never measured how far it is from our little town in east-central Alberta to Newcastle. My only frame of reference then was the ancient expression “carrying coals to Newcastle,” although I had no idea what that meant. I did know that we had to traverse the southwestern quarter of Saskatchewan, travel the full Mercator's depth of Montana and reach northeastern Wyoming. It was as incomprehensible to me then as Zimbabwe is today.

My Dad was the school principal in our town. His salary was $90 a month. There were seven of us, including my baby sister and three brothers. We had a 1929 Model A Ford. Naturally, it was decided that we would all go, and that we would go by car. Only our dog, Wimp, would be left at home, at the mercy of the neighbors.

|

I have little recollection of Saskatchewan, perhaps because it was a continuum of Alberta and therefore unremarkable. Except that the roads were not exactly like today's Interstate System, nor yet the Trans-Canada Highway. Montana was more of the same, perhaps hotter, perhaps more sere. Life inside the car was intolerably suffocating unless you were a kid. Bob, 14, read mostly or looked out the open window. Jack and Ron, just older and younger than me, caught the marauding grasshoppers that flew in and taunted me with them, knowing of my squeamishness. Carol slept, mostly, held by my Mother, in front with Dad.

Somewhere In Montana, I remember a brutally hot afternoon. We had no water in the car. There was a grey unpainted farmhouse just off the road, unfenced, unattended by any accompaniment except for a shed-like barn in the rear. The woman who came to the door wore a simple shift, her hair straggled. I remember that from my slight eye-level she was barefoot and had few teeth.

“Could we possibly get a drink?” my Dad asked.

“Why, sure enough, dearie,” she said. She gestured. “It's around to the back. He'p yourself.”

|

At the rear of the house there was a cistern like a small swimming pool, of ancient crumbling concrete. There was a rusted pail, attached to a rope. Hunching over the edge, we could see what looked like a foot of brown water in the cistern's bottom. There was a smell I could not identify, worse than any farm smell back home.

“Get in the car, boys,” my Dad said.

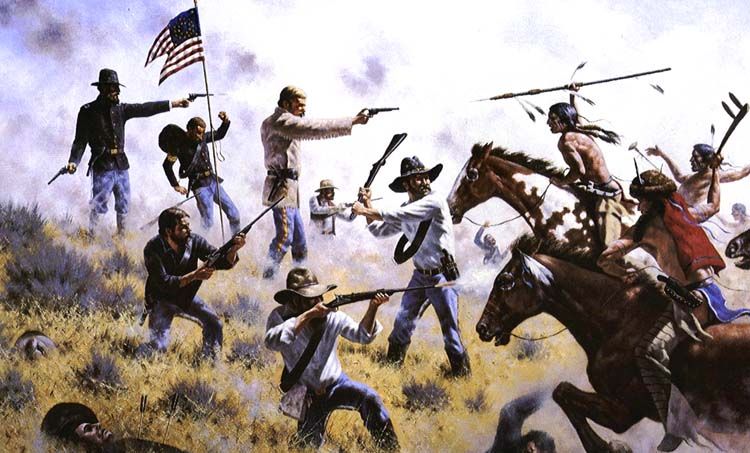

As we proceeded farther south, I remember Dad's lectures about Custer and the Little Big Horn off to the East somewhere near, factual and unbiased as always, I suppose, but I was too young to grasp nationhood or Indians, anyway. I don't remember how we stopped over each night, whether simple auto courts or hotels. I do remember the locusts, clouds that dimmed the sun at times, or made the road greasy.

And then we arrived, and to me the world of my American cousins was familiar but strangely warped, perhaps like a hand-held camera. Their town was larger than ours, and just as poor, huddling in the hot summer of what was still the Great Depression, but it was somehow more cool in a modern sense, I can only use the word glamorous. We had a swimming hole in our creek back home, sod-dammed and muddy, but usable. My cousins' swimming hole east of town was a magic pool surrounded by the rocky bed of a small river – you could cannonball off a ten-foot outcrop.

|

And they had a refrigerator and ice cubes. One of my cousins' friends worked in a Cocoa-Cola plant, and they got Cokes from him sometimes, for nothing. We knew about Coke back home, but who could afford it?

On the trip home, Dad told us we would head west, just for the change, deciding to go up through Great Falls to Calgary and then home. Somewhere near Cheyenne we came upon the biggest event, what today we would call the game-changer.

It was what much later we would call a tourist trap, but few had the energy or the will in those days to think about such things. Just outside a small town, there were a few buildings with a sign of some sort out front. There was a corral, with an open gate, and rearing out of that gate, suspended in time and space and on its hind legs, was a saddle bronc, a real horse, humped ferociously, in mid-buck, although unmoving.

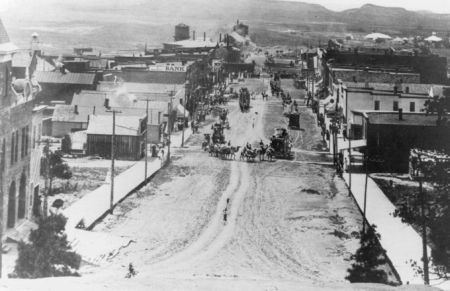

Circus visits Newcastle long ago- exact year unknown |

The bronc was of course stuffed, supported by an unseen metal pipe that fixed it to the fence post. A grinning cowhand leaned nearby, waving a tourist welcome. It appeared that for a fee, the amount of which I don't remember, one could be seated in this rearing saddle and be photographed.

My brothers and I did, all four of us, one at a time, while Dad, with his even then ancient expandable Kodak snapped our individual pictures. Jack of course posed the most dramatically, left fist twisted in the reins, pulling leather while he gestured dramatically with his outstretched right hand. We couldn't wait – chortling with the joke, the subterfuge with which we would wow, impress, overwhelm our envious friends back home. “Yeah, I rode this saddle bronc in Wyoming – look, that's me in the picture, isn't it?”

It was our mainstay, our anticipated relish, which we hugged inwardly all the way back to Alberta. But to collapse the suspense, I'll reveal the tragedy now: Dad had forgotten to remove the portrait attachment from the lens of the Kodak. As a result, all four snapshots blurringly revealed what looked like a corral, all right. What could clearly be seen as a bucking horse emerging from the gate, all right, and something that clearly looked like a cowboy astride the plunging horse. But certainly, unconvincingly, not necessarily, Bob, Jack, Ron or Bill. Our trip, our triumph, our talking point had evaporated.

I've always thought that our journey, that way, that summer, taught me about the ambivalent North American life I would lead in the seven decades that have followed. How it is to live on both sides of our border and especially how my Dad – although raised on New York's lower east side - remained so essentially Canadian: fiercely protective of us on the one hand, but yet with a decided reticence, a way, deliberate or otherwise, of dimming the picture of ourselves, unlike our American cousins in their cool and studied assertiveness.

Because it was ultimately Dad who brought it all off, who took my Mother to her dying sister, who carried whatever it was that was needed, and yet that which was superfluous, to Newcastle. He had a Canadian blend of courage and risk-taking, tinged with a touch of the requisite insanity in his vision.

I think he taught us somehow to come out of the chute as Jack had, waving triumphantly and yet pulling leather at the same time.

Bill Annett grew up a writing brat; his father, Ross Annett, at a time when Scott Fitzgerald and P.G. Wodehouse were regular contributors, wrote the longest series of short stories in the Saturday Evening Post's history, with the sole exception of the unsinkable Tugboat Annie.

At 18, Bill's first short story was included in the anthology “Canadian Short Stories.” Alarmed, his father enrolled Bill in law school in Manitoba to ensure his going straight. For a time, it worked, although Bill did an arabesque into an English major, followed, logically, by corporation finance, investment banking and business administration at NYU and the Wharton School. He added G.I. education in the Army's CID at Fort Dix, New Jersey during the Korean altercation.

He also contributed to The American Banker and Venture in New York, INC. in Boston, the International Mining Journal in London, Hong Kong Business, Financial Times and Financial Post in Toronto.

Bill has written six books, including a page-turner on mutual funds, a send-up on the securities industry, three corporate histories and a novel, the latter no doubt inspired by his current occupation in Daytona Beach as a law-abiding beach comber.

You can write to Bill Annett at this address: bilko23@gmail.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Articles for May 1, 2012 | Articles for May 2, 2012 | Articles for May 3, 2012

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

[Return to Top]

©2026 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.