Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Jul-09-2012 20:25

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

The Volunteer Spirit

Paul Keats for Salem-News.comEven though he has lived in Mandalay, Rangoon and now the U.S., Win Min says that he hasn’t changed, describing himself as always the villager.

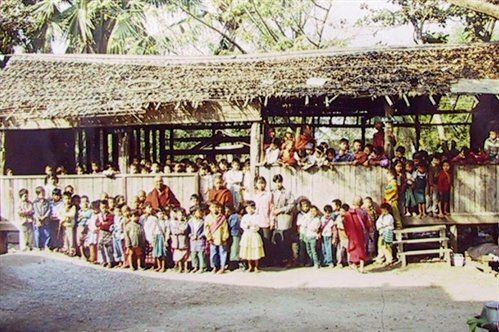

Min doing relief work in his native Burma |

(EUGENE, OR.) - With the recent election of Aung San Suu Kyi to the Burmese parliament and the loosening of international sanctions, Win Min has watched the events in his home country with both hope and longing.

“Right now a small little door is open,” he said. “We need to look at it to see how we can make the small little change a bigger change.”

Min remains half a world away in Eugene, where he has been a student at the University of Oregon since October 2010. A committed community activist who organized relief efforts after the 2008 typhoon that devastated his country, being away from home at this historic time has been trying for the 25-year old. He remains determined, however, to earn a bachelor’s and master’s degree and to return home “as soon as possible” to put his education to work helping the people of his country.

The need for education has been a common theme in Min’s life. Growing up in a poor farming family in a small village in western Burma where cars are rarely seen, he sold snacks at primary school to help pay for classes at a state-run school where students are required to pay tuition.

His mother would encourage him and his brother to study in the evenings after long days at school by making them mango salad. This “little bit of sour,” as he explains, would help them overcome exhaustion to continue studying.

In his last year of primary school, he was assigned to study one of eleven stories for homework. When his teacher asked him the next day which story he had chosen, he replied, “All eleven,” and then recited each from memory. “I wanted to show what I could do,” he said. “I wanted to be a good student.”

|

|

The old school Min attended |

Min wanted badly to go on to secondary school, which he says is every student’s dream in Burma. Even though he had saved some money, the cost of sending both him and his older brother was too much for his family to afford. His parents thought it best that he help with the farm because he was good at business and knew many people.

To avoid seeing secondary school students going to and from school in the green and white uniform that he had hoped to one day wear, Min started his farm work extra early at 5:30 a.m. and returned home very late.

Just eleven years old, he was the youngest farmer among men who included his father and uncle. Using cows rather than tractors to work the land, they farmed in the traditional way to grow rice, beans, wheat, peanuts, sesame, and chile peppers. Despite the disappointment of not being in school, he saw the work as educational. “I got to understand the real life of farmers,” he said, recalling how the lack of rain can mean the loss of everything.

Min also learned how difficult it is to make money farming, given the uncertainties of weather and interest rates for agricultural loans. When the slow season came in summer, he decided to go to Mandalay to seek work. He found jobs making flip flops and biscuits, but was able to earn just $7 per month. Wherever he looked for work, he was asked about his level of education.

“I realized that without education, you cannot get good money,” he said.

The new school Min attended |

Before coming to the city, he had met a Buddhist priest in his home village who told him of a monastery school in Mandalay where he could continue his education at no cost. Min decided to go to the school, where he enrolled and remained for 10 years. When he began, the school consisted of a bamboo building that was too small for all the students, so many studied outside under the trees.

During his time there, the school grew from 1,125 students to 4,700 students. Today, thanks to donations from Japanese citizens and the Japanese government, the school educates upwards of 7,000 students, most of whom come from neighboring villages.

Min made rapid progress in his studies, eventually teaching English and training other teachers. Unlike the rote learning that was used in the primary school, he was able to ask questions and have a dialogue with teachers, as well as participate in numerous activities with the community. The monastery school’s experiential approach to education, where you are “welcome to open your own thinking,” taught Min that life itself is education.

The monastery school system in Burma is a free alternative to the state-run schools where students pay tuition rates which, set by each school’s administrative officials, can vary widely. The students who attend are from poor backgrounds. Many are orphans from the civil war zones on the border with Thailand, who speak very little Burmese but are welcomed in to be housed and educated.

The monastery school teachers are former students volunteering their services to carry on the work of educating those with few means. Min’s school also included a hospital and child nutrition center, and the school even purchased bicycles for children in neighboring villages to get to and from school. “The school was for everyone, and everyone could study for free,” Min explained. “It’s a great school.”

When Buddhist monks protested the military government’s polices in 2007, Min was living at a monastery in Rangoon and conducting teacher training courses at the US Embassy. He was inspired by the actions of the monks and wanted to be involved in what would come to be called the “Saffron Revolution.” “Monks work for the welfare of the people,” he explained. “When monks started protesting, the people followed.”

Carrying a voice recorder and notebook, he closely followed the protests of the monks and the subsequent reactions of the military. What he saw horrified him. “We live in a Buddhist country, and I couldn’t really believe that they were going to hit and shoot the monks,” he said. “It was so shocking. I have seen people beating one another before, but they were beating the monks and the women brutally.”

|

International journalists were not spared the brutality, either. When Japanese photojournalist Kenji Nagai was shot by a soldier just blocks away from the Sule Pagoda, Min was on an adjacent street corner and witnessed the killing. This experience was a turning point for Min. Growing up, he had learned that the army was there to protect the country, and although he had heard of the army killing people in areas of ethnic fighting, he never believed that it would be turned upon the monks, who are highly respected by the people and serve as the country’s moral authority. “All we saw was soldiers hitting people. What’s going on?” we said.

Each day of the protest, Min would pass along the information he had gathered to the US Embassy, who sent it to media outlets such as the BBC or CNN. Min noted how, thanks to the Internet and electronic media, the world was able to learn what was happening, in contrast to the student protests in 1988 that went unreported and resulted in many students being imprisoned by the government. In 2008, Min was working at the American Center in the US Embassy in Rangoon as the leader of teacher development.

He and his co-teachers would go to villages to train volunteer teachers and would also invite teachers to come to the Center for training. There was such a strong response from teachers in wanting to promote community teaching that he began to wonder how they could involve young people in volunteer work. With help from the British Council, where he was taking classes, he and fellow teachers decided to form a youth volunteer network that eventually came to be called the Civic Society Initiative. They established an elderly care project and recruited students who were studying at the British Council.

Traveling to a very poor area of Rangoon, they went from one tent-like structure to another, giving food and talking to old people who had no one to care for them. Min explained to the students that what they were giving to these people may not alter their material life, but it would “help them feel that their survival is still valued.” He encouraged the students to call them ‘grandmother’ and ‘grandfather,’ even though they were not blood relatives, stressing the importance of caring for the human family.

“I was trying to help them understand what volunteering was like, the volunteer spirit,” he said.

|

Min in traditional dress |

Volunteer work, however, often conflicted with the reality of needing to earn money that Min could send back to his family. Because of his natural leadership and organizing abilities, others looked to him to perform volunteer roles of ever-increasing responsibility.

The aid organizations that he worked with encouraged him to take a salary from the donations he received from them, but he explained that doing so would run counter to the volunteer spirit and set a poor example. “People trusted me and I wanted to help them understand volunteering,” he said. “If I’d taken a salary from the donations, other volunteers wouldn’t have trusted me anymore.”

Min credits his monastery school experience with instilling in him the humanitarian values that guide his work. He noted how his school ran many community projects, such as providing housing, food, medical care, education and clothing to homeless street kids, as well as giving free medical aid to the poor parents of students. His involvement in such efforts taught him that “We are all together, and we are all creating our society equally.”

The number of volunteers for Min’s organization continued to grow, eventually branching into separate groups for teaching and teacher training, cooking and food delivery, and medical aid. The medical aid group was composed of medical students who had graduated and wanted to become involved in what he was doing.

Min was able to arrange for donations of medicines from American firms, which the students used for treating the elderly. Min’s hope is that these student volunteers, who are from wealthier backgrounds and will go abroad to study at foreign universities, will carry on this type of community work when they return to Burma.

Cyclone Nargis hit Burma on May 2 of that same year, claiming 138,000 lives, according to Burmese government figures. It was the deadliest named cyclone of the North Indian Ocean Basin and the worst natural disaster in the recorded history of the country. Wondering what he and his volunteer network could do to help, Min and several friends went to the Irrawaddy River Delta, scene of the cyclone’s worst impact.

Because the Burmese government did not want other countries to see the extent of the devastation, security was extremely tight. “The military was everywhere,” Min said, recalling how soldiers patrolled the villages and were posted on street corners. He and his friends managed to get through, though, but upon seeing what he described as “dead bodies everywhere,” they didn’t know what they could do.

|

They returned to Rangoon, where Min applied for funding and soon received $5,000 from the British Embassy. He emailed volunteers, who joined him and often brought along relatives to help. His group grew very large and he was soon coordinating teams to collect, pack, and arrange the transport of food and clothing donations.

He went to many organizations to raise additional funds and continued to collect food that didn’t need to be cooked, as there were no means for cooking in the disaster zone. He also helped coordinate teams of medical students and arranged for donations of medicine from the US. “Time was very important,” he said. “Every minute we were saving lives.”

In the months that followed, Min made many trips back to the Irrawaddy River Delta. Providing aid was declared illegal by the government, and wherever they went, the military questioned them as to who they were and what they were doing. He had guns pointed at him numerous times and was told, “Either you leave or we have to shoot you.”

Nevertheless, they persisted in bringing aid. “We were doing humanitarian work and helping our own people,” he said. “We didn’t think what we were doing was illegal.” Sometimes they were required to leave the supplies they had brought with the military, never knowing if they would ever be distributed.

The military, he explained, cared only about the release of information that would reveal it had done nothing to help the people. For six straight months, Min worked every day to coordinate the delivery of aid to the cyclone victims.

Min performing relief work |

In January of that year, before the cyclone hit, Min had attended an English teaching conference in Thailand where he represented the US Embassy in Rangoon as the leader of teacher development.

While there, he met representatives from the University of Oregon’s American English Institute, who suggested a possible scholarship that could bring him to Eugene to study. Min eventually received an invitation letter from UO and an offer of scholarship through the International Cultural Service Program.

Because of his involvement in the cyclone relief efforts, however, he was unable to go. The invitation and scholarship remained open, and in 2010 he finally received his admission letter and immigration documents. After consulting with friends who encouraged him to go and offered to help pay for his visa fee and plane ticket, he made the decision to study in the US.

Min is currently earning a bachelor’s degree in Planning, Public Policy and Management, which will allow him to work more effectively with NGOs for community development projects in Burma. As part of the ICSP scholarship, Min and other international students go into the local community to teach about their cultures and to learn about American culture outside of the university. He has gone to pre-schools, high schools, and elder care homes to talk about Burma and the values of community-mindedness and helping others.

He views Eugene as relatively friendly and a good community, and he likes the “green and rain” because it reminds him of home. Coming from a culture where people freely share what they have, he has realized that “Americans value physical things too much,” and he wonders what percentage of people “are happy right now.”

|

|

He explains how in Burma, “Caring for others is more important than caring for yourself. We are taught to feel the way that other people feel. If someone is hungry, we are taught to feel that. Community value is very high in my country.”

Having studied a year and a half at the university, Min sees American higher education as being very good at conducting and teaching research. However, he feels students also need to go see what is happening around the world and in their own community. Research, he says, is only useful if it can be taken from the textbook and brought into the real world.

“I don’t think education is only in the class, “ he said. “Education is everything you can learn by working and helping people.” He notes how in America, despite its political ideals, people do not seem to have a sense that they are not all being treated equally, citing a recent classroom discussion in which many of his fellow classmates were unaware of social and economic inequalities in the US. Part of the reason for this, he believes, is that it is mostly kids from wealthier backgrounds who have access to higher education.

Even the financial aid that is available, he says, seems largely based on grades, and students from more privileged backgrounds have better means to acquire good grades.

Higher education is one example of what he sees as a large gap between those with access to resources and those without. “Only a minority, a few people, have access, and they have access to everything,” he said. “The majority of people don’t have much. What is going on here is pretty different from what I expected.”

He is heartened, however, by the recent discussion of the 99% vs. 1% that was prompted by the Occupy Wall Street protests, describing it as a “scary moment” for the US. “Other countries have been discussing inequalities for years, but Americans have not,” he said.

He hopes that this recent awareness will continue to grow and lead to change. “I think that American people need to understand that they all need to look for the change together,” he said. “They cannot just wait for the government to make the change.”

One of Min’s long-term goals is transforming the educational system of Burma so that people can have free education to develop the critical thinking skills necessary to understand what is happening in their country. For the moment, however, people are suffering from poverty and lack of jobs, issues that he says need to be addressed first. “Many people are jobless,” he said.

“No job means no money, and no money means no food. If people are worried about food, they cannot think about education.”

While Min believes that the international sanctions against his country have increased the suffering of the people, he concedes that they have also worked to shift the government’s isolationist policies. With the easing of sanctions, he predicts that the government will take advantage of the increased foreign trade and investment, taking a portion of it, but that many jobs will also be created, which will help the people.

Helping the people is what Min hopes Aung San Suu Kyi, whom he calls “Our Lady,” can achieve by working with the government. He would like to see conditions changed such that people can ultimately “get an education and have a voice.” That change doesn’t necessarily have to be democracy, though. He explained that the majority of people in Burma don’t understand about democracy.

More than anything, he says, people want a change from the military government that has been suppressing them and taking everything out of the country while the rest of the people are suffering.

“If anyone is doing good for the country, we’ll accept that leader, whoever it is,” he said.

At twenty-five years of age, Min has been away from home for nearly fourteen years, ever since he walked ten miles to the bus station “carrying a small little bag” and rode for a whole day on the roof of a bus to journey to the city. Even though he has lived in Mandalay, Rangoon and now the United States, he says that he hasn’t changed, describing himself as always the villager.

When he finishes his education here, he hopes that his time abroad will not be seen as a problem by the Burmese government, even though he came to the US legally with a visa. Overall, he remains optimistic about his return, as he does with so many things. “Whatever difficulty, home is home,” he said. “So I am going home.”

-------------------------------

Tweet

Follow @OregonNews

Articles for July 8, 2012 | Articles for July 9, 2012 | Articles for July 10, 2012

Salem-News.com:

Quick Links

DINING

Willamette UniversityGoudy Commons Cafe

Dine on the Queen

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

MUST SEE SALEM

Oregon Capitol ToursCapitol History Gateway

Willamette River Ride

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

Historic Home Tours:

Deepwood Museum

The Bush House

Gaiety Hollow Garden

AUCTIONS - APPRAISALS

Auction Masters & AppraisalsCONSTRUCTION SERVICES

Roofing and ContractingSheridan, Ore.

ONLINE SHOPPING

Special Occasion DressesAdvertise with Salem-News

Contact:AdSales@Salem-News.com

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

Sandra July 18, 2012 6:41 pm (Pacific time)

Excellent article about an inspiring young man.

Roger July 15, 2012 7:48 am (Pacific time)

Min is one of the good people on this Earth! He will do good things for Burma!

Sura July 10, 2012 10:39 pm (Pacific time)

I knew Min was special from his amazing work at AEI...and now I see he is truly incredible. What an inspiring and beautiful story - I feel blessed to know you, Min!

Kayla July 10, 2012 3:42 pm (Pacific time)

Min is an amazing person...everyone at the AEI can vouch for that! :-)

Bamar July 10, 2012 2:42 am (Pacific time)

Very good article. Thanks! to Min for planning to coming home.

[Return to Top]©2026 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.