Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Dec-08-2011 01:43

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

The Avenue of Missing Women

Salem-News.comWhy isn't Ciudad Juarez disclosing the real numbers of Murdered women and girls?

There are big questions about why the number of female bodies in morgues are not being fully disclosed. |

(LAS CRUCES, N.M.) - Shot and wounded in a December 2 incident outside her home, Ciudad Juarez teacher Norma Andrade was released from the hospital this week.

A decade ago, Andrade became an outspoken activist after her 17-year-old daughter, Lilia Alejandra Garcia, was kidnapped, tortured and brutally murdered.

Along with others, Andrade founded Nuestras Hijas de Regreso a Casa (May Our Daughters Return Home), a group that protested the disappearance and killing of young women in a troubled border city.

In trips across the border, Andrade familiarized US audiences with the stories of Lilia Alejandra and hundreds of other murdered young women.

Although Andrade had largely retreated from public activity in more recent years, another daughter and fellow activist, Malu Garcia, stayed in the public limelight.

Last February, she was forced to flee Ciudad Juarez after threats and an arson attack on her home.

The Andrade shooting was swiftly condemned by Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission, Amnesty International and dozens of other Mexican human rights organizations. In the aftermath of other attacks on Mexican activists, the groups are clearly alarmed.

|

Norma Andrade |

“Malu and Norma are not isolated cases and part of a concerning and disturbing trend about the cost of justice and speaking out,” Maureen Meyer, Mexico and Central America program associate for the non-profit Washington Office on Latin America, told Frontera NorteSur.

According to a press account, Garcia had requested protection for her family one week before Norma Andrade was shot. After leaving the hospital, Andrade was reported to have police protection; law enforcement officials also said they were seeking a suspect in the crime. Initially, the Chihuahua state prosecutor’s office tied the shooting to a botched car-jacking attempt by unidentified suspects.

Garcia promptly blamed organized crime for the attack on her mother and linked it to a specific complaint filed with state authorities earlier this year over the operation of a human trafficking network that was abducting young women from downtown Juarez. The authorities were provided with names and businesses involved in the network, Garcia told the Mexican press.

Separately, the family of 18-year-old Jazmin Ibarra Apodaca family filed a similar disappearance report last June when the young woman vanished after saying she was going to a modeling job interview. Months later, in October, state law enforcement officials finally issued a public alert for two unnamed men who were allegedly connected to the disappearance of Ibarra.

“The men approach young women and try to convince them to work with a modeling agency that offers excellent benefits,” the Chihuahua state prosecutor’s office was quoted.

The assault on Norma Andrade happened amid an end-of-the-year spurt in the overall violence ravaging Ciudad Juarez. For instance, on Wednesday, December 7, as many as 16 people were reported murdered even before the day was over. And the Andrade attack came as new scandals were emerging over the long-running disappearance of girls and young women from Ciudad Juarez.

Ciudad Juarez |

No reliable, single set of statistics exists to pinpoint the total number of young females who have vanished in the city since the late 1980s and early 1990s, when such disappearances became widely known, but figures mentioned by government agencies and non-governmental organizations range from the dozens to the hundreds.

“The situation becomes complicated if (relatives) try to find missing persons, because they are afraid to complain to the authorities for fear of reprisals,” said Elizabeth Flores, director of Pastoral Obrera, the social action arm of the local Roman Catholic Church.

In an interview with Frontera NorteSur, Flores said the examples of Marisela Escobedo, the Ciudad Juarez mother who was gunned down across from the Chihuahua governor’s office while campaigning to bring her daughter’s murderer to justice one year ago, or Nepomuceno Moreno, the Sonora father who traced the 2010 disappearance of his son to police prior to being murdered himself in broad daylight near state government offices last month, stand as vivid warnings, Flores said.

On September 16 Avenue, an important thoroughfare leading into downtown Ciudad Juarez, dozens if not hundreds of posters of missing young women cover utility posts and walls. Some of the pesquisas are older,-Silvia Acre disappeared since 1998, for example- while others are much newer.

|

Lining block-after-block, the small, grainy pictures contrast with the large “happy face” posters plastered on the concrete embankments of the nearby Rio Grande as part of a project this fall to uplift the image of Ciudad Juarez. Yet only weeks later, the “happy face” exhibition is falling prey to the elements and disintegrating rapidly in the bitter cold of an oncoming, predicted hard winter, ironically not unlike the missing posters of young women on September 16 Avenue.

Adriana Sarmiento |

On Friday, December 2, 15-year-old Adriana Sarmiento was buried. Disappeared in 2008, the teen’s body was recovered in the rural Juarez Valley in November 2009 but left sitting in the city morgue until a Los Angeles newspaper story revealed that Sarmiento’s corpse had been identified for months.

The report was news to Sarmiento’s family, which immediately contacted the authorities and got Adriana’s body back for proper burial.

“Completely heartless” is how Sarmiento’s mother, Ernestina Enriquez Fierro, characterized officials to an El Paso Times reporter. “We are like puppets on the authorities’ hands.” Enriquez described her daughter as a happy and energetic student who studied at Allende Preparatory School in downtown Ciudad Juarez, a private institution previously attended by several other female victims of disappearance and murder.

Arturo Sandoval, spokesman for the Chihuahua state prosecutor’s office, acknowledged law enforcement officials had tentatively identified Sarmiento back in April but held off on notifying the family until a US lab confirmed DNA samples at the end of November.

|

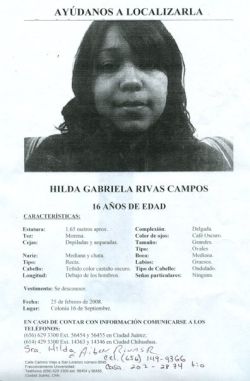

Sarmiento’s family was not alone in Ciudad Juarez in finding out that missing loved ones had been in the morgue for long spells of time. The families of Hilda Gabriela Rivas, 16, and Monica Delgado, 17, underwent similar experiences this year.

“(Sarmiento) recalls the practice of hiding remains by the government of Chihuahua at the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s,” the Chihuahua City-based non-governmental organization Justice for Our Daughters said in a statement. “It is worrisome there could be bodies of women and girls secreted away in official installations.”

Pastoral Obrera’s Elizabeth Flores said the failure of authorities to publicize the bodies amounted to a “state crime.”

“The prosecutor’s office should disclose information about the bodies it has in the morgue, even if they are unidentified,” Flores added. “It can’t hide this information from public opinion, much less the victims’ families. We don’t know how many more of the young women they’ve been looking for over the years are in there.”

According to the Los Angeles media account, the Ciudad Juarez morgue recently contained 26 bodies of unidentified women, including 15 victims who were discovered with signs of extreme violence in a single mass grave in the Juarez Valley. However, the state prosecutor’s office would only confirm up to seven possible victims found in separate graves in the same area.

In the last four years, the Juarez Valley has been the scene of battles between competing crime syndicates, mass displacement, house-burnings and even an arson attack on a church. Army and Federal Police patrols have combed the zone during this time.

Like the Lote Bravo and Lomas de Poleo sections of Ciudad Juarez, which served as dumping grounds of femicide victims in the 1990s, the Juarez Valley is slated for new development including a new international border crossing and an industrial/housing complex promoted by Industrial Global Solutions of Mexico City and the US company Prudential.

|

It’s important to keep in mind that the latest reports of unknown female homicide victims stacked up in the morgue follow a backlog of cases from previous years.

From 2005 to 2009, the internationally-recognized Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team, worked under contract with the Chihuahua state attorney general’s office in a project to identify the remains of suspected female murder victims from both Ciudad Juarez and Chihuahua City.

According to team member Mercedes Doretti, the specialists succeeded in identifying 33 victims but could not identify 50 others from both cities, mainly from Ciudad Juarez.

The team was working with lists of disappeared women provided by both government and non-government sources as well as DNA samples from families of local persons who generally went missing from 1993 to 2005, with some cases from 2008 or early 2009, Doretti said in a phone interview for this story.

“The impression we have is that (earlier unidentified victims) are from out-of-state or out-of-country,” Doretti said. “This is a hypothesis we have.”

Even as the Sarmiento Plus scandal sizzled away, another controversy erupted over the Mexican government’s compliance or non-compliance of the 2009 sentence issued by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in relation to the cotton field murder case of three young women in 2001.

Another image of Adriana Sarmiento |

On Friday, December 2, the same day Norma Andrade was shot and Adriana Sarmiento buried, the state prosecutor’s office announced the arrest of 33-year-old Eduardo Chavez as the alleged murderer of Esmeralda Herrera Monreal, one of the cotton field victims.

“The detention of the cotton field woman killer complies in part with the sentence issued by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights against the Mexican state,” read a headline in the local Norte newspaper.

Chavez protested his innocence, and a lawyer for the families that took the Mexican government to the Inter-American Court, Karla Michele Salas, also cast doubt on the government’s case. The cotton field affair has been marked by a series of arrests of suspects who later turned out to be scapegoats, most of whom were released.

In almost an anti-climax to a heady week, members of the Mexican Congress’ latest anti-femicide commission arrived in Ciudad Juarez.

In a visit to the new memorial to the cotton field.victims, they criticized the conduct of government officials responsible for investigating the disappearances and murders of women, which have mounted during the past two decades despite numerous probes and recommendations from congressional commissions, United Nations and international human rights organizations. The lawmakers also asked for forgiveness from a traumatized society.

|

|

Legislator Teresa del Carmen Inchaustegui Romero, president of the congressional special commission, called the cotton field a painful place connected to the “holocaust of women, of girls, of adolescents, that Ciudad Juarez is suffering.”

The violence, she said, not only originates with organized crime but is also “institutional” in the sense that justice remains undone.

Lucia Lagunes Huerta, general director of the Mexican City-based Cimacnoticias women’s news service, took a broad swipe at the recent events in Ciudad Juarez. Lagunes referenced her comments by citing a new study that documented the murders of 34,176 women in Mexico from 1985 to 2009.

Titled “Femicide in Mexico,” the report was authored by the College of Mexico, United Nations, National Women’s Institute and the Mexican Congress’ femicide commission.

According to Lagunes, only three percent of women’s murders are investigated.

For government officials to ask public forgiveness, Lagunes wrote, specific crimes have to investigated and punished while “any form of gender violence” is likewise duly sanctioned.

“If this does not happen,” Lagunes contended, “the petition of pardon becomes one more joke from a state that is not committed to women.”

Additional Sources:

- Cimacnoticias. December 2, 5 and 6, 2011. Articles by Anayeli Garcia Martinez, Patricia Mayorga and Lucia Lagunes Huerta.

- Lapolaka.com, December 3, 5, 6, 7, 2011.

- El Paso Times, December 4, 2011. Article by Juan Antonio Rodriguez.

- Proceso/Apro, December 2 and 5, 2011. Articles by Mauricio Rodriguez and editorial staff.

- El Diario de Juarez, December 1, 2011.

- Los Angeles Press, November 29, 2011. Article by Guadalupe Lizarraga.

- Milenio.com, November 26, 2011.

- La Jornada, October 25 and 26, 2011; December 2 and 3, 2011. Articles by Ruben Villalpando.

- Norte, October 26, 2011; December 2 and 3, 2011. Articles by Felix A. Gonzalez, Herika Martinez Prado and editorial staff.

Frontera NorteSur: on-line, U.S.-Mexico border news

Center for Latin American and Border Studies

New Mexico State University

Las Cruces, New Mexico

Articles for December 7, 2011 | Articles for December 8, 2011 | Articles for December 9, 2011

Salem-News.com:

Quick Links

DINING

Willamette UniversityGoudy Commons Cafe

Dine on the Queen

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

MUST SEE SALEM

Oregon Capitol ToursCapitol History Gateway

Willamette River Ride

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

Historic Home Tours:

Deepwood Museum

The Bush House

Gaiety Hollow Garden

AUCTIONS - APPRAISALS

Auction Masters & AppraisalsCONSTRUCTION SERVICES

Roofing and ContractingSheridan, Ore.

ONLINE SHOPPING

Special Occasion DressesAdvertise with Salem-News

Contact:AdSales@Salem-News.com

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

[Return to Top]

©2026 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.