Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Aug-05-2011 18:47

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

They Die, We Die: An essay on life and...

By Daniel Johnson, Deputy Executive Editor, Salem-News.com“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main; if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less..."

|

(CALGARY, Alberta) - Amy Winehouse died last July 23. She was 27, the same age as Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix, the rock icons of my generation were, when they died. Coincidence? I think not.

At birth we join society (in progress) as a nascent thread; when we exit society, we leave a rip in the social fabric.

John Steinbeck observed in one of his novels: “When two people meet, each one is changed by the other so, you’ve got two new people.” Society is created and sustained by these ongoing interactions of its members—a non-stop fluxion of interrelationships.

Nobel economist Milton Friedman, for example, described Henry Simons as:

“...my teacher and my friend—and above all, a shaper of my ideas. No man can say precisely whence his beliefs and his values come—but there is no doubt that mine would be very different than they are if I had not had the good fortune to be exposed to Henry Simons”.

I can describe my own experience. I wrote in my journal in 1993:

“In 1967 I met a fellow named Brian when I worked at the Post Office. He left after the summer to go to the [University of Calgary] and I didn't really stay in touch with him. Then, in 1968 I was working as a laborer at [CP Rail] and we met by chance in the yards and rekindled our friendship. He became my closest friend until he was killed in a car accident in 1970. Brian was a very mentally healthy guy and going through my journal I saw the trend of how he was influencing me in many positive ways. He would, in a straightforward way, point out things that I did that were inappropriate or counterproductive and I was learning from him. I actually started to change my behaviours under his influence. If he had not died, I don't know how things would have gone, but I am sure they would have gotten better.”

Perhaps the most well known example of this phenomenon is seen in Frank Capra’s 1946 movie It’s a Wonderful Life. Although fictional, it rings absolutely true. George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart) attempts suicide as a result of what he believes to have been a failed life. He is rescued by an angel, Clarence, who takes him to an alternate world where he had never been born so he can see the positive and far reaching effects his living actually had.

In the story, the druggist’s son has died and when filling a prescription Mr. Gower abstractedly includes the wrong medication. The young George Bailey notices the error, points it out and the correct prescription is sent out. In the world with no George Bailey in it, however, the wrong prescription goes out, a child given it dies and Mr. Gower, convicted of manslaughter, serves time in prison. After his release, he, once the town’s respected druggist, becomes the town drunk.

A feel good movie, but the situation works both ways. How different would the world be today, had Napoleon never been born? Adolf Hitler? Stalin? Or you—think of it in the Capraesque sense?

(This suggests an interesting counter-scenario. Think of all the mistakes and “bad” things you’ve done. Like Mr. Gower, you did them because there was no George Bailey-equivalent born to have corrected you or diverted your attention to prevent the act. This heads us down the road of unsubstantiated flight of the imagination, but I still wonder…This looks the subject of another piece.)

You’ve heard the expression, and surely even experienced it yourself: After I met so-and-so, I was no longer the same person”.This raises the intriguing question: If a person is a sum of all the people with whom they have interacted, from where does the I actually originate? Put another way, if I am, today, the culmination of all the people with whom I have interacted, all the books and stories I have read (as indirect and secondary interactions), then who am I? If Friedman had never met Simons, who would he have become? If I had never met my some particular individuals who significantly influenced me, Brian as a potential example, who would I be today?

Think of who you are now: If you had had a different teacher (or two) in school; if your parents had settled in a different neighborhood and you grew up with a different group of friends, who would you be today?

Who we are I suggest, is an unconscious extension of the community in which we were raised and in which we live. We see this most clearly when we consider the very public figures (usually from movies) that have been in our lives. We take on their mannerisms, styles of speech and dress, becoming, in a very real way, an extension of their public persona.

What makes me think of this is the number of people you see around you (perhaps you even do it yourself) who hang their sunglasses by one arm over the front of their shirt or blouse. When I was a teenager and young man, that was never done. What movie star in what movie did that originally and almost immediately it was copied throughout a segment of society?

Historian Garry Wills describes the importance of sociability and society. Of Robinson Crusoe, he says

“Daniel Defoe’s character was post-social, in the sense that he brought with him into his accidental isolation not only many artefacts of the culture that formed him—guns, an axe, saws, nails, etc. from the shipwreck—but also the skills and concepts formed in that culture, his calculation of times and seasons, of means to accomplish tasks without a long process of trial and error over what works and what does not. He had an accumulation of practical knowledge (which things are edible, which animals are useful, how to make and control fire, and so on). The society he left not only made his axe, which was so useful to him as a weapon or tool. It made him. He knows what to do with the axe, how to build with it, keep it from rust, turn it to things it can accomplish most efficiently. He learned all those things through prior social intercourse, before he was isolated. In order to imagine a truly pre-social individual, we would have to think of a Crusoe with total amnesia about the world he had left without any artefacts from that world.”

We are all part of a greater whole, said the 16th century metaphysical poet John Donne whose life overlapped with that of William Shakespeare. He is primarily remembered today for this meditation:

“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main; if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friends or of thine own were; any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

Astronaut Sandra Magnus, from the ISS, echoed this viewpoint in an interview from space:

“Up here I've seen the world from a different viewpoint. I see it as a whole system, I don't see it as a group of individual people or individual countries. We are one huge group of people and we're all in it together.”

But our interconnections are not constants. Jaques, the melancholy lord in Shakespeare’s As You Like It said in this familiar quote:

“All the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players: They have their exits and their entrances; and one man in his time plays many parts.”

Many parts, yes. We are not fixed in our personalities, attitudes or beliefs; we are not the same person we were yesterday; last month, ten years ago. Looking at the arc of a life, this is clear to any person who has even a modicum of self-awareness. Similarly, we appear to be different to different people. To a child we are a parent; at work we are bosses, co-workers or employees. At school we are students or teachers. And so on. This applies to our relationships with virtually all the people in our lives.

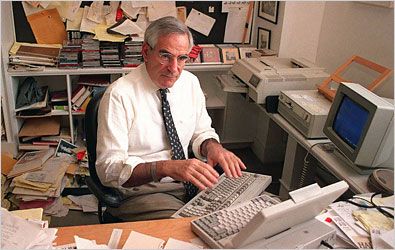

This essay begin to germinate in my mind a few years ago when I learned that Pulitzer Prize winning journalist and author David Halberstam had died in a car accident on April 23, 2007 near San Francisco. Kevin Jones, a Berkeley journalism graduate student who was driving him to an appointment, made an unsafe left turn and Halberstam was killed instantly. The subsequent arc of Jones’ life became irrevocably changed at the moment of the accident—the inverse of the Steinbeck truism—when two people unmeet; when a person dies, all the people to whom they are connected are also changed. This is the tear in the social fabric. We experience this in our own lives when our formative connections are severed—grandparents, parents, relatives, siblings and friends die, until it is our own turn—and our exit affects those down the line of existence.

David Halberstam (1934-2007)

Although I never knew him or talked with him, I had spent many weeks with him over the years, reading, noting and digesting four of his 19 books: The Best and the Brightest (1972), The Powers that Be (1979), The Reckoning (1986), and The Fifties (1993). He contributed significantly to my understanding of journalism, politics and society as a whole. Out of all that reading and note taking, one anecdote stands out which I still occasionally repeat.

The Reckoning is an historical overview of the auto industry in the United States and Japan (focusing on Ford and Datsun—now Nissan) where he described the 1970 North American introduction of the legendary Datsun 240Z. In Japan it was called the Fairlady and Yutaka Katayama, president of Nissan Motors USA, knew that such a name would have an uphill battle in attracting significant numbers of American buyers. In business, the Japanese were exceptionally deferential to their superiors, so even questioning the name was not appropriate. Katayama’s solution was to take the Fairlady name off and replace it with a plate that said 240Z which was the company’s internal designation for the model. He obeyed and disobeyed at the same time. I love that story.

James Aurness (1923-2011)

This was a vague essay until I read of the recent death of James Arness—Marshall Dillon of the longest-running TV western Gunsmoke (1955-1975—635 episodes). I probably watched about 300 of those shows, week after week. Such a constant influence surely affected, even in a small way, who I am today—as well as the tens of millions of other viewers over the years.

It’s the sharing of such cultural constants that solidifies our social life. How many millions of people had something in common to talk about the morning after an episode of Gunsmoke or, pick your TV show or movie.

What came out of this was the news (to me, at least) that James was the older brother of the actor Peter Graves who was the rancher in the 1955-1960 series about a boy and his horse, Fury, then later as the head of Mission Impossible, 1966-1973. Graves became better known again later, spoofing himself in the Airplane movies (“Joey, have you ever been in a Turkish prison?”.) Their birth name was Aurness.

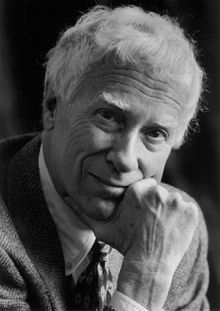

Peter Falk (1927-2011)

As I continued to gather notes, I read of Peter Falk, famous as the TV detective Columbo, who died on June 23/11.

A little known fact about Falk was that he had a glass eye (his eye had been surgically removed when he was three because of retinoblastoma). There was a story he frequently told: After being called out at third base during a baseball game in high school, he removed his glass eye and handed it to the umpire. “You’ll do better with this,” he said.

When I was in elementary school, I knew a kid named Raymond (last name forgotten) who also had a glass eye. Although I only heard the story and never saw him do it, he apparently used to take it out in class and roll it around on his desk.

Then there’s the joke about the man who lost an eye and couldn’t afford a glass replacement. He was sensitive about this and became an almost complete recluse. One day a friend said to him: Hey, I know this guy, a carpenter. He can lathe a little block of wood into a globe and we’ll paint it and you can stick it in your empty socket, and it will look almost normal.

So, that’s what they did. He ended up with a wooden eye that looked almost real.

His friend then suggested he get out of the house after his long isolation and they go to a dance. The guy was reluctant, but agreed to go. At the dance, he found himself sitting self-consciously by himself against the wall. Then he noticed a really homely woman sitting by herself on the opposite wall. “She couldn’t refuse me,” he thought to himself, so he walked over.

Standing in front of her, he said, “Would you like to dance?”

Her face lit up as she responded, “Would I? Would I?”

He jumped back, pointing at her, “Pig face, pig face!”

Finally: I had a dentist appointment one day and walking down the hall to the office, I noticed a sign on a door for Ocular Prosthetics. I remarked to the dentist’s receptionist that I thought that was a pretty puffed-up way to describe glasses or spectacles. No, she said, they supply glass eyes. Bada boom. A very minor change in my life over about half a minute. Think of that sort of experience multiplied millions of times over a lifetime!

We think we are psychological individuals but we’re really not. We exist at the psychological interface of all the relationships and experiences we have had with other human beings over a lifetime. (A person who lives to age 70, lives through more than 2.2 billion seconds. Millions of opportunities for “minuscule” influences that accumulate into the formation of a psychological person.)

The relationships also apply to animals in our life—primarily our pets, but it goes beyond that. Irene Pepperberg, an animal psychologist, now at Brandeis University, bought a Grey parrot at a pet shop in 1977. Alex (she named him) was about a year old. She worked with him for nearly 30 years, discovering in her research that animals have far more intelligence than humans have ever given them credit for. His language abilities were equivalent to a 2-year old child and he had the problem solving skills of a 5-year old. He had a vocabulary of 150 words, knew the names of 50 objects and could count up to seven. “Alex didn’t have the use of language the way you and I do,” Pepperberg said. So I can’t prove he had a degree of consciousness. But the way he behaved surely was suggestive”.

Then, she want on to say,

“Alex taught me to believe that his little bird brain was conscious in some manner, that is, capable of intention. By extrapolation, Alex taught me that we live in a world populated by thinking, conscious creatures. Not human thinking. Not human consciousness. But not mindless automatons sleepwalking through their lives, either.”

Through the course of the research she and Alex formed a deep, mutual emotional bond where she said that, while Alex depended completely on her for everything, she never had the feeling that she “owned” him.

At the end of their workday on Sept 5, 2006, as Irene was putting Alex in his cage he said (it was almost the same ritual, every day): “You be good. I love you.” Those were the last words he said to her. The next morning he was found dead in his cage. (For the full story of Alex, see Irene Pepperberg’s book, Alex & Me (2008) Out of all the books I’ve read in my life this is one of the very few I recommend to everyone looking for a story that is both heart-warming and inspirational).

Even Pepperberg pondered the theme I’m exploring: “Had I gotten a different Grey that day back in 1977, Alex might have spent his life, unknown and unheralded, in someone’s spare bedroom”. Not to mention how different her life would have become—as Friedman with Simons.

Question: What to do with the dead?

There are more of them than us (about five to one by some estimates). Philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff said he realized after his son had died, that he already loved many among the dead: Beethoven, Mozart, Shakespeare—a long list.

There are more of them than us (about five to one by some estimates). Philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff said he realized after his son had died, that he already loved many among the dead: Beethoven, Mozart, Shakespeare—a long list.

This essay could just as well have been called “Connections”. About a month before Halberstam died, American physicist Albert Baez died. I’d never heard of him but there was a surprising connection. His two daughters were Joan and Mimi. (I don’t need to tell you who Joan Baez is). Mimi was married to Richard Farina who in 1966 published the cult classic Been down so long, it looks like up to me. I read that book in the late 1960s and the scene in the college cafeteria still resonates with me as one of the funniest, most outrageous scenes ever. Two days after its publication he attended a book signing and that evening, at a surprise 21st birthday party for Mimi, he spontaneously took a joy ride with someone on their Harley. In a wipeout, he was thrown from the back and killed instantly. He was 29.

Then, there’s Canadian-born economist John Kenneth Galbraith who died in April 2006. Until I reduced my library a few years ago, I had copies of every one of his books and had read them all (some more than once) and had made extensive notes. As with Halberstam, there is a Galbraith story that I repeat occasionally as an anecdote. It’s about alleged freedom of the press.

“In any large organization there are only differing degrees of restraint. And the fact that it is often self-restraint or self-censorship does not make it any less confining. Self-censorship at Fortune, I learned, involved a constant calculation as to whether a particular statement—sometimes a sentence or a paragraph—was worth the predictable argument, perhaps with [Time-Life founder Henry] Luce, possibly with some frightened or zealous surrogate. Often one decided that it was not the day for a fight. Or if your conscience was compelling, you couched the favorable reference to Roosevelt or the CIO in such careful language that it would slip by, overlooking the near-certainty that it would slip by all your readers as well.”

This is another good example of how others shape our actions and, subsequently, who we become.

In the early 1980s me and a few others started an independent magazine, The Public Eye (which ran for four issues) and I got the idea to interview him. I got his home number and called. His wife answered, I asked for him, and he came to the phone. Incredible!

Unfortunately, I was so in awe of the man that I was completely intimidated. I asked a few questions and he, with decades of experience, didn’t exactly brush me off, but kept me at arm’s length with a series of non-answers. The conversation lasted perhaps ten minutes and, sorry, nothing there to publish although he did send me a letter (still in my files) telling me that if I was ever in that part of the world, to look him up and we could have a lunch.

On February 18, 2006. Billy Cowsill died here in Calgary. I didn’t even know he was living here! Newly drug-free and sober he had been estranged from his family who only learned of his death while holding a memorial for his brother, Barry, a victim of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and whose body had not been found and identified until the month before Billy died

My connection to him is The Cowsills (family group) hit of the late 1960s, “The Rain, the Park and Other Things”. That song is on one my nostalgia play lists that I put on from time to time when the world gets a little too heavy. Those were golden years—but only in retrospect. (The Cowsills were the inspiration for the TV show, “The Partridge Family”.)

I can’t bypass Kurt Vonnegut, who died in 2007. I had read all his books but my favorite is Breakfast of Champions (1973). It was made into a movie starring Bruce Willis, but I have no interest in seeing it (even though I am something of a Willis fan). This is because important books to me become their own worlds and I cherish that, not wanting them be distorted or destroyed by someone else’s imagination. That’s why I won’t watch the movie versions of The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings and a few others.

The most interesting part (and one of the funniest) of B of C, is Vonnegut’s description of Dwayne Hoover’s (Willis) breakdown in a hotel bar. By this time, Vonnegut has put himself into the storyline as one of the bar patrons, so he could see the action up close. Too close, it turned out. When the fracas starts he doesn’t get out of the way in time and someone, stepping back quickly, lands a heel on his foot and breaks a toe.

My favorite quote from B of C is Vonnegut’s description:

“As three unwavering bands of light, we were simple and separate and beautiful. As machines, we were flabby bags of ancient plumbing and wiring, of rusty hinges and feeble springs.”

One person with the most influence on my life was Albert Einstein (although he had influenced many others, much more significantly). He died in 1955 when I was nine years old and I was completely unaware of his exiting the social fabric. There would have been widespread media coverage but I came from a lower working class environment and it was not the kind of event that would have garnered any attention or discussion.

Then there are those of whom I knew, but who died and I had no awareness of it. In 1965 I bought a copy of William Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage. It was originally published in 1915 and I suppose it became prominently available as a 50th anniversary edition. I remember reading it during lunch and coffee breaks at work that fall, unaware that Maugham himself was living through his last weeks (he died on December 16, 1965).

I began my lifelong study of physics as a teenager and read about the giants of the field. In my mindset of the time, they were just parts of history. I didn’t realize until many years later many of them were still alive. Erwin Schrödinger did not die until1961 (age 73) a couple of years after I began studying physics. Werner Heisenberg in 1976 (age 74) and Paul Dirac in 1984 (age 82). These three men were the principle architects of quantum physics. Then, there was Max Born who died in 1970 (87). A Nobel physicist himself, his main influence on me was introducing me to a serious study of Einstein’s relativity through his book Einstein’s Theory of Relativity (what else could he have called it?) I had read his book in 1969.

I could go on with other people who had significant influences on the arc of my life, but I think I have adequately established my thesis. Now I arrive at a very controversial aspect (in some minds) of being human: the interface between individuals and groups. That they are symbiotically related is beyond dispute.

Medical essayist, Lewis Thomas, in A Long Line of Cells wrote that

"The most intensely social animals can only adapt to group behavior. Bees and ants have no option when isolated, except to die. There is really no such creature as a single individual; he has no more life of his own than a cast-off cell marooned from the surface of your skin."

What I have essentially been arguing is that we feel like individuals, but we are actual extensions of our society. In fact, without society (other people) we would not exist at all beyond a basic animal level. This has been demonstrated through the phenomenon of feral children—children raised by animals outside human society.

In defining our social place, said philosopher Alan Watts:

If the definition of a thing or event must include a definition of its environment, we realize that any given thing goes with a given environment so intimately and inseparably that it is more and more difficult to draw a clear boundary between the thing and its surroundings.

To put the importance of socialization in perspective, consider feral children, raised in isolation from other humans. Fiction writers have often depicted children raised by wild animals, such as the legendary Romulus and Remus, abandoned as children and raised by wolves and who, after they were rescued by a shepherd, grew up to found Rome; Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s "noble savage" or Edgar Rice Burroughs’ "Tarzan, lord of the apes". Real feral children, however, are the exact opposites of their fictional counterparts. There are documented cases of children raised in isolation from human groups and all behaved more like wild animalsthan humans. They could not speak—in some cases could no longer even learn to speak—and reacted to humans with fear and hostility, walked hunched or on all fours, tore into their food like wild animals, were apathetic to their surroundings, and were unable to keep even the lowest standards of personal hygiene. Society plays a decisive role in the emotional, mental and cultural lives of biologically individual human beings.

People and groups have properties like salt. For a few crystals, any change in the number of crystals represents a large percentage change—from ten crystals to 15, for example is a 50 percent increase; salt behaves here as a collection of distinct pieces of matter. When the number of crystals is measured in the millions, however, adding or subtracting a handful of crystals has essentially no measurable effect. Salt then behaves like a liquid and can be poured. It flows and takes on the dimensions of its container. Its granularity becomes unimportant yet we must remember that a bag of salt, for all its continuous-like behavior, is ultimately granular.

Many species practice social behavior. A good example of social creatures whose very survival is locked into their interdependence is the bee colony. A bee colony comprises three different types of bees: queens, drones, and workers, each of whom perform complementary tasks for survival. No individual bee could survive on its own. They are so interdependent, that one could say the entire colony is the real organism; subdivisions of it do not exist independently. Deepak Chopra makes this analogy:

The body itself is not a fixed package of atoms and molecules—it is a process, or rather billions of simultaneous processes being coordinated together. I once watched with fascination as a beekeeper reached into a swarm of bees and, by gently enfolding the queen in his hands, moved the whole hive, a living globe of insects suspended in midair. What was he moving? There was no solid mass, but only an image of hovering, darting, ever-changing life, which had centered itself around a focal point. The swarm exists as an outcome of bee behavior. It is an illusion of shape behind which the reality is pure change.

Such are we, too. We are a swarm of molecules hovering around a center, but with diminishing confidence. The old queen, the soul, has decamped, and the new queen seems reluctant to hatch from her cell. The great difference between us and a swarm of bees is that we find it hard to attribute reality to the unseen center that holds us together. It is obvious that one does, for otherwise we would be flung apart into chaos. But a queen looks like any other bee, only larger, while we cannot hope to find a lump of cells that contains what we consider to be central to us—love, hope, trust, and belief.

Consider the Kanizsa triangle. Visually, it is three black circles with a segment removed from each. The result is an expanse of nothing that appears to block out a shape as if it is inscribed in ink. This “nothing”, overlaying the three circles gives us the illusion that we can “see” a triangle.

Analogously, we are Kanizsa beings in that we are a psychological expanse of relationships and experiences overlaying a social reality. When you look at a group of people, you can “see” individuals that have the same “reality” as a Kanizsa triangle. Without the group, we are undefined—we don’t exist. A simple thought experiment demonstrates this. Imagine that, after you were born, you were immediately put into the wild and raised by animals—wolves or coyotes, say. If you come into human society ten or fifteen years later, “who” are you? You have no identity, no consciousness of a “self”, no ego, no place in the social web. You exist biologically, but no differently than all the other wild animals of the world. Google “feral children” and you will find documented cases of children brought up by animals who, when they were returned to human society, were completely unsocialized. Depending on their age, some of them could no longer even learn to speak even though the physiology for speech was there. Society has made you (as all of us) who you are as a social being. I suggest, that it is the belief in, and pursuit of such faux individualism that is the source of much of society’s discord and dysfunction.

There’s another way to look at our alleged individuality.

Where and what is an individual? A whirlpool or vortex in a river, for example, has a definite location in space and persists through time. It is even possible to generate in a river special sorts of waves, called solitons that behave in many respects like particles—even to the extent of colliding with each other and bouncing away.Yet these vortices and solitons have no independent existence apart from the river that supports them. The vortex exists through the act of being constantly created. The fountain in a city park and every living cell in the body are not fixed, rigid structures but maintain their features through constant flux. The flow of water through the fountains or whirlpool gives it permanence; the flow of matter through a cell keeps it alive.

Like a vortex (whirlpool), we are the confluences of an enormous range of current and past psychological influences and, like a vortex, we are not constant. Memory gives us the illusion of physical and ego continuity. As astronomer George A. Seielstad describes it, echoing Watts:

"Since everything is the product of its environment and since the environment is always changing, what an object is depends upon when it came into being ."

This is where our feeling of individuality comes from. We are all “created”—whatever that will come to mean—in differing environments. Two siblings, five and six years old, for example, have different parents. The younger sibling has parents who are older, with more experiences, and parents in different life circumstances than when the older sibling was at the same age.

Continued in Part 2: “The Undiscovered Country”

For instant paper writing help on life topics you can check SmartWritingService - professional essay services which will not let you down online.

Born and raised in Calgary, Alberta, Daniel Johnson as a teenager aspired to be a writer. Always a voracious reader, he reads more books in a month than many people read in a lifetime. He knew early that in order to be a writer, you have to be a reader.

Born and raised in Calgary, Alberta, Daniel Johnson as a teenager aspired to be a writer. Always a voracious reader, he reads more books in a month than many people read in a lifetime. He knew early that in order to be a writer, you have to be a reader.

Another early bit of self-knowledge was that writers need experience. So, in the first seven years after high school he worked at 42 different jobs ranging from management trainee in a bank (four branches in three cities), inside and outside jobs at a railroad (in two cities), then A & W, factories and assembly lines, driving cabs (three different companies), collection agent, a variety of office jobs, John Howard Society, crisis counsellor at an emergency shelter, salesman in a variety of industries (building supplies, used cars, photocopy machines)and on and on. You get the picture.

In 1968, he was between jobs and eligible for unemployment benefits, so he decided to take the winter off and just write. The epiphany there, he said, was that after about two weeks, “I realized I had nothing to say.” So back to regular work.

He has always been concerned about fairness in the world and the plight of the underprivileged/underdog. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that he understood where that motivation came from. Diagnosed with ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder) he researched the topic and, among others, read a book Scattered Minds by Dr. Gabor Maté, an ADD person himself. Maté wrote: "[A] feeling of duty toward the whole world is not limited to ADD but is typical of it. No one with ADD is without it."

That explains his motivation. Hard-wired.

As a professional writer he sold his first paid article in 1974 and, while employed at other jobs, started selling a few pieces in assorted places. He created his first journalism gig. In the late 1970s, when the world was recovering from a recession, the Canadian federal government had a job creation program where, if an employer created a new job, the government would pay part of the wage for the first year or two. The local weekly paper was growing, so he approached the publisher and said this was an opportunity for him to hire a new reporter. The publisher had been thinking along those lines but cost was a factor. No longer.

Over the next 15 years, Daniel eked out a living as a writer doing, among other things, national writing and both radio and TV broadcasting for the CBC, Maclean’s (the national newsmagazine) and a host of smaller publications. Interweaved throughout this period was soul-killing corporate and public relations writing.

It was through the 1960s and 1970s that he got his university experience. In his first year at the University of Calgary, he majored in psychology/mathematics; in his second year he switched to physics/mathematics. He then learned of an independent study program at the University of Lethbridge where he attended the next two years, studying philosophy and economics. In the end he attended university over nine years (four full time) but never qualified for a degree because he didn't have the right number of courses in any particular field.

In 1990 he published his first (and so far, only) book: Practical History: A guide to Will and Ariel Durant’s “The Story of Civilization” (Polymath Press, Calgary)

Newly appointed as the Deputy Executive Editor in August 2011, he has been writing exclusively for Salem-News.com since March 2009 and, as of summer 2011, has published more than 150 stories.

He continues to work on a second book which he began in 1998.

View articles written by Daniel Johnson

Articles for August 4, 2011 | Articles for August 5, 2011 | Articles for August 6, 2011

googlec507860f6901db00.html

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

Natalie August 6, 2011 6:08 pm (Pacific time)

Ooops... Stephen will be heartbroken, guys, and he gets nasty in that mood.

COLLI August 6, 2011 3:24 pm (Pacific time)

Well stated, well written, and oh so true.

By the way, congratulations on the "Deputy Executive Editor" assignment Dan.

Thanks for your appreciative comment Bob.

julieasmith August 6, 2011 2:47 am (Pacific time)

“The foundation is going to help thousands of people. That is Amy’s legacy,” Mitch Winehouse, Amy’s father, tweeted Wednesday. http://bit.ly/qdFLy7

[Return to Top]©2026 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.