Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Apr-24-2012 00:36

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

The Wall, 10 Years on / Part 4: Trapped on the Wrong Side

Haggai Matar Special to Salem-News.comWe live in something that is part jail, part hell,” Qasab Sha’ur says bitterly. Sha’ur is a resident of Arab a-Ramadin, and has to go through the fence at least once or twice a day.

Project Photography: Oren Ziv / Activestills |

(TEL AVIV +972Mag) - This is exactly the kind of thing that planners of the route hoped to avoid: having Palestinians who are barred from entering Israel trapped on the “Israeli” side of the fence. Yet in its long and winding route, the fence engulfs some 35,000 Palestinians who describe their new lives as a daily prison.

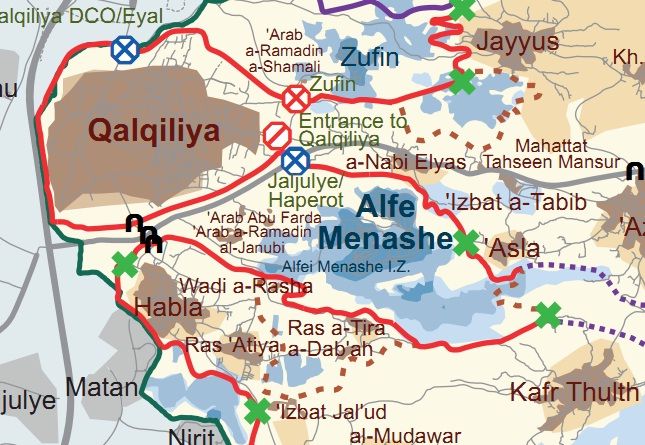

March 2009. Residents of the small village Wadi a-Rasha in the Qalqiliya district have mixed feelings. On the one hand – their High Court victory is as precedent in the history of the wall – for the first time ever, construction crews are here to build a new route for the fence and to demolish the old one. The news fence frees them from a life they felt was paramount to prison – engulfed in the Alfei Menashe enclave and detached from the rest of the West Bank. On the other hand – the new route leads to the uprooting of more olive trees, and most of the village lands are trapped on the “Israeli” side of the fence

The villagers decide to fight the new route as well, demanding that the fence be moved to the Green Line, just two kilometers to the west. Small non-violent demonstrations take place almost on a daily basis: Israeli and international activists block the bulldozers, get beaten and arrested, are banned from the district (I myself was subject to the pleasure) and constriction continues. As time goes by, the fence is erected, and like so many other places, the legal battle for permits to cross it begins. This is yet another example of the reality of the gradual detachment of people from their lands, described in chapter three.

Villager overlooking Wadi a-Rasha lands |

March 2012. I decide to return to Wadi a-Rasha as part of my work on this project. I see how hard it is to get to the village, the road now going through a long detour and various checkpoints, taking at least three times as long as before. However, I notice an even tinier village that is apparently still on the western side of the fence, and decide to look into it. Apparently, the Wadi a-Rasha petition to the court was joined by four other villages – Ras Atiya, Habla, Arab Abu-Farda and Arab a-Ramadin – and while the first three partially received what they had asked for, the latter two were to remain inside the thin strip between the fence and the Israeli border. Some 1,000 people live in the two villages, and they are all doomed to be disconnected from their wider community for the foreseeable future.

Two kilos of tomatoes – no more

“We live in something that is part jail, part hell,” Qasab Sha’ur says bitterly. Sha’ur is a resident of Arab a-Ramadin, and has to go through the fence at least once or twice a day. “Our village is small, just 500 people, and it had no hospital or clinic, no school, no big shops or workplaces, so everything requires crossing the checkpoint. But going through can take an hour, at best. Coming by car, you have to empty your vehicle completely, send every little thing through an X-ray machine. Then the car is checked manually, then a dog takes a sniff around, and then any fluid you have has to be sampled and examined at a laboratory they have there – this includes water and olive oil. This is what my daily ride home looks like.”

Strange as it may seem, this actually describes a best-case scenario, in which the content of the car and the passenger are ultimately allowed through. In many other cases, the villagers have to deal with strange limitations on what may or may not be brought from the other side. For example, retuning home from shopping with more than two kilograms of tomatoes leads to a short investigation, ultimately requiring a special permit from the army’s District Coordination Office. Meat and eggs require a permit from the Israeli Ministry of Agriculture. Friends, doctors, ambulances, servicepersons and relatives cannot go through at all.

“Since the checkpoint, the Eyal Terminal, as they call it, is the last buffer before entering Israel, the authorities consider it a proper border crossing, even though it is not on the Green Line and there are both Jewish settlers and Palestinians on the other side,” says attorney Michael Sfard, who represented the villages in court. “Now we’ve finally reached a status quo that allows people to bring groceries through for personal consumption – but the definition of that term is negotiable. It’s hard to begin to explain the implications of this on people’s lives, as one would have to break down every single part of a person’s life to see how harsh the fence is on it.”

The Alfei Menashe enclave. The wall is in red, the old route in dotted brown. Arab a-Ramadin is in the center (Map: B'Tselem) |

As mentioned before, Arab a-Ramadin is trapped in the same enclave as the settlement of Alfei Menashe – but the fence running around them both is the only thing these two places have in common. The village, founded in the late 50s by Bedouins who were forced out of the Negev, has no proper roads, no running water and no electricity (“even though the pipes and power cables go under and above their heads to Alfei Mensashe,” stresses Sfard), and there are standing demolition orders against of its houses. Villagers can physically walk or ride into Israel unchecked, but if caught, they can go to prison. There is separation even in the checkpoint, as settlers go through a fast lane with no questions asked, and Palestinians go through the process described above. “I try to tell the army that all residents of the enclave should at least share the same lane at the checkpoint, but I know the mere thought of Israelis and Palestinians being treated equally is totally foreign to the army’s way of thought,” says Sfard.

The new fence near Wadi a-Rasha (Oren Ziv / Activestills) |

Arab a-Ramadin and Arab Abu-Farda are not alone. To the north, there is also Bart’a – recently visited by Yuval Ben-Ami’s in his Round Trip - also trapped in a fence enclave. Looking south, one encounters the villages of Hussan, Wadi Fukin, Nahalin, Batir and Al-Jab’a, which are to be surrounded by the Gush Etzion fence from the east and another one to the west. Further south, the West Bank village of A-Seefer is caged by the fence of the South Hebron Hills. According to B’Tselem, 35,000 Palestinians are either already trapped on the wrong side of the wall, or will be if and when its construction ends. This does not include residents of East Jerusalem. “The Palestinians will never allow for even a single village to be annexed to Israel,” determines Colonel (res.) Shaul Arieli, a member of the Council for Peace and Security. “I have no idea why they would build a fence on such a route that would clearly have to be changed and rebuilt – at least because of these villages”.

Meanwhile in Arab a-Ramadin, the villagers see nothing but a bleak future ahead of them. “You know, most of us had to change our way of making a living,” tells me Sha’ur. “Once, most people had sheep, the village was full of them, but now we only have 10 percent of our pasture lands left, and you can’t get the sheep across the fence. So the livestock had to be sold, and now we work for the PA. or as simple workers elsewhere around the West Bank, and have to cross the checkpoint every day.

“Three years ago, the Civil Administration contacted us, and offered us a transfer into the West Bank. Ever since, they keep on offering. The land we sit on belongs to us, and they offered us to exchange lands on the other side of the fence. But the West Bank is under occupation, and I am no settler who will take someone else’s land while backed by the Israeli Civil Administration. A Palestinian can’t just do that, nor is there any reason for us to move. It’s the fence that has to move to the Green Line.”

Previous chapters in this series:

Part 1: The great Israeli project

Part 3: An acre here and an acre there

Haggai Matar is an Israeli journalist and political activist. After writing for the short-lived Palestine Times and for Ha'ir Tel Aviv he is currently working as the municipal correspondent of Zman Tel Aviv, the local supplement of Ma'ariv, and is a prominent writer at the independent Hebrew website MySay.

In 2002 Matar was part of the Shministim (Seniors') Letter to then PM Ariel Sharon, and was imprisoned for two years for his refusal to enlist to the Israeli army. Since his release he has been active in various groups against the occupation, as well as in several class-based struggles within the Israeli society.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Articles for April 23, 2012 | Articles for April 24, 2012 | Articles for April 25, 2012

Quick Links

DINING

Willamette UniversityGoudy Commons Cafe

Dine on the Queen

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

MUST SEE SALEM

Oregon Capitol ToursCapitol History Gateway

Willamette River Ride

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

Historic Home Tours:

Deepwood Museum

The Bush House

Gaiety Hollow Garden

AUCTIONS - APPRAISALS

Auction Masters & AppraisalsCONSTRUCTION SERVICES

Roofing and ContractingSheridan, Ore.

ONLINE SHOPPING

Special Occasion DressesAdvertise with Salem-News

Contact:AdSales@Salem-News.com

Salem-News.com:

googlec507860f6901db00.html

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

[Return to Top]

©2026 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.