Publisher:

Bonnie King

CONTACT:

Newsroom@Salem-news.com

Advertising:

Adsales@Salem-news.com

~Truth~

~Justice~

~Peace~

TJP

Mar-10-2010 21:45

TweetFollow @OregonNews

TweetFollow @OregonNews

Cosmology of the Ants

Daniel Johnson Salem-News.comIt appears that billions of Argentine ants around the world all actually belong to one single global mega-colony.

Courtesy: Farm4.static.flickr.com |

(CALGARY, Alberta) - As children, it’s natural for us to believe the world is flat. Everything around us is flat. If we live on a prairie, the world stretching away looks flat; everything just gets smaller in the distance. No mystery there.

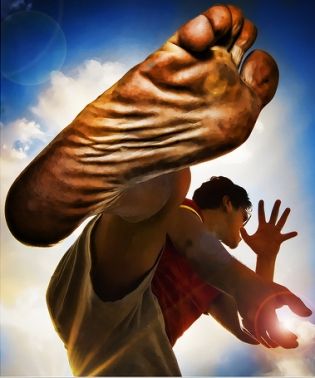

Courtesy: audienceoftwo.com |

But see in your mind's eye what the world looks like from an ant’s point of view. Blades of grass would tower overhead, just as trees do for us in the middle of a forest. The primary challenge for an ant culture would be to see the lawn for the grass. Out on the lawn, molehills would become mountains.

Assuming an ant/human ratio of a thousand to one, the Earth's circumference would be (in our terms) 25 million miles. A worker ant's lifespan is one to three human years—Jules VernAnt would have written a novel: "Around the World in 80 years". Exploration by land would mean journeys of hundreds of ant years. An AntBus 380 would take about 40 ant generations to circumnavigate the globe.

The earth’s surface area (land, water and ice) is about 200 million square miles. From an ant’s perspective that would be about 200 billion square miles. No shortage of room for anthills. In fact, they are already extensively populating the earth.

Ants in your yard. Ants in your basement. We have no real conception of how pervasive ant culture is around the globe. Scientists have learned that a single mega-colony of ants has colonised much of the world.

Argentine ants living in vast numbers across Europe, the US and Japan belong to the same inter-related colony, and do not fight one another, as unrelated ants do. The colony may be the largest of its type ever known for any insect species, and may rival humans in the scale of its world domination.

In Europe, one vast colony of Argentine ants is believed to stretch for 6,000 kms (3,700 miles) along the Mediterranean coast, while another in the U.S., known as the "Californian large", extends over 900km (560 miles) along the coast of California. A third huge colony exists on the west coast of Japan.

It appears that billions of Argentine ants around the world all actually belong to one single global mega-colony.

Some ant facts

'Ant's Point of View' courtesy: painting.about.com |

- Ants are studied by myrmecologists

- More than 12,500 species are classified with an upper estimate of species at 22,000

- Lewis Thomas: "All of us are able to smell ants, for which the great word pismire was coined."

- Ant societies have division of labour, communication between individuals, and an ability to solve complex problems—the latter of which is lacking in many human societies

- Ants are found on all continents except Antarctica and only a few large islands such as Greenland, Iceland, parts of Polynesia and the Hawaiian Islands have no native ant species

- Ants can “see” ultraviolet light

- In the Book of Proverbs in the Bible, ants are held up as a good example for humans for their hard work and cooperation

- The eggs of two species of ants are the basis for the Mexican dish called escamoles. They are considered a form of insect caviar and can sell for as much as $40/lb

- In areas of India, and throughout Burma and Thailand, a paste of the green weaver ant is served as a condiment with curry

- Mashed up in water, like lemon squash, these ants form a pleasant acid drink which is enjoyed by the natives of North Queensland

A final observation: Is there any cosmic significance to the the fact that Antarctica is the only continent that has no ants? Just wondering.

Cosmology of the ants

Essayist Lewis Thomas observed:

"A solitary ant, cannot be considered to have much of anything on its mind; indeed, with only a few neurons strung together by fibers, he can't be imagined to have a mind at all, much less of a thought. He is more like ganglions on legs. Four ants together, or ten, encircling a dead moth on a path, begin to look more like an idea. they fumble and shove, gradually move toward the Hill, but as though by blind chance. It is only when you watch the dense mass of thousands of ants, crowded together around the Hill, blackening the ground, that you begin to see the whole beast, and now you observe it thinking, planning, calculating. It is intelligence, a kind of computer, with crawling bits for its wits."

What will be the form of intelligence arising from hundreds of billions of ants connected on a global basis? Let’s find out.

Considering that, from an ant's point of view, virtually the entire Earth would be terra incognita, what would their picture of "the universe" look like?

Some ants are photosensitive, i.e., cannot come out in daylight. So, at night, they would first wonder about what was visible to them—the sky above. Here their minute size compared to humans would make no difference at all. Once they were able to get out into an open area, the sky would look the same to them as it does to a thousand-times-larger human being.

An antsview of the Earth would be similarly speculative. The ants' understanding of their universe would be, like ours, based on a series of assumptions. The basic assumption in our science-oriented society is that our universe began in what physicists call the Big Bang, pinned down, as of 2010, to 13.7 billion years ago—137 million centuries.

But, says science writer Stephen Strauss, “the psychological reality is that the cosmos is more and more frightening the further we get from Earth.” The same would be true for ants—the farther they get from the anthill.

Cosmology is the branch of astronomy dealing with the origin, composition and evolution of the universe. Physicist Alan Lightman calls cosmology "the grandest and most speculative of all sciences [sitting] at the boundary between what is considered science and what is not."

From a cosmic point of view, there is no difference in size between the ant and the human so that our cosmologies will be the same.

Albert Einstein said, "It is the theory that decides what we can observe." Put another way, it is the assumptions that we hold, consciously and unconsciously, that are the filter through which we interpret the world we “see”. Charles Darwin is a prime example.

Cwm Idwal (pronounced koom idwal) is a hanging valley in the Glyderau range of mountains in northern Snowdonia, the national park in the mountainous region of North Wales. Its main attraction is to hill walkers and rock climbers, but it is also of interest to geologists and naturalists, given its combination of altitude (relatively high in UK terms), aspect (north-facing) and terrain (mountainous and rocky). In a 2005 poll, Cwm Idwal was ranked as the seventh greatest natural wonder in the UK.

Cwm Idwal seen from the shores of Llyn Idwal Credit: Mick Knapton |

In his autobiography, Charles Darwin said:

“We spent many hours in Cwm Idwal, examining all the rocks with extreme care, as Sedgwick [his companion] was anxious to find fossils in them; but neither of us saw a trace of the wonderful glacial phenomena all around us; we did not notice the plainly scored rocks, the perched boulders, the lateral and terminal moraines. Yet these phenomena are so conspicuous that…a house burnt down by fire did not tell its story more plainly than did this valley. If it had still been filled by a glacier, the phenomena would have been less distinct than they are now.”

Because Darwin and his companion were not psychologically prepared to see glaciation, they did not see it. This, basically, is the story of science over the last four centuries. Things are not seen until people are psychologically ready to see them. This applies equally to each of us in our individual perceptions.

Darwin was also able to see something that wasn’t there. In 1837 he visited a section of the Scottish Highlands, the so-called “parallel roads” and decided that the ledges were beaches that had been formed when the glen had been filled by an arm of the sea and published a paper about it in 1839. Over the next twenty years, however, the idea of at least one Ice Age seemed, to most geologists, to be the source of the ledges. Darwin was receptive to the idea of an Ice Age, but still maintained that the ledges were the result of a lake. In 1861 he suggested that the geologist Thomas Jamieson should visit the site and resolve the matter. He did and said that Darwin was wrong. Darwin wrote to him: “Your arguments seem to me conclusive...I give up the ghost. My paper is one long gigantic blunder...I have been for years anxious to know what was the truth, & now I shall rest contented, though ashamed of myself.”

Assumptions are passed on from teacher to student and from one generation to the next.

In 1862 Lord Kelvin speculated on the source of the sun’s heat and how long it might be expected to shine. He concluded:

“It seems, therefore, on the whole most probable that the sun has not illuminated the earth for 100,000,000 years, and almost certain that he has not done so for 500,000,000 years. As for the future, we may say, with equal certainty, that inhabitants of the earth can not continue to enjoy the light and heat essential to their life for many million years longer unless sources now unknown to us are prepared in the great storehouse of creation”.

This, of course, was three quarters of a century before the discovery of nuclear energy. In 1933 physics Nobelist Ernest Rutherford, known as the father of nuclear physics, said: “Anyone who expects a source of power from the transformation of… atoms is talking moonshine.” But, writes biologist Lewis Wolpert in The Unnatural Nature of Science: “Today’s moonshine is tomorrow’s technology, and it is with technology and politics that the real responsibility lies. Even so, one must guard against taking scientific ideas as dogma and treating science as infallible.”

In the 1890s a debate arose between physicists and geologists over the age of the earth. Kelvin argued that, from the cooling rate of the earth as estimated from measurement of heat in mines, the earth must have been nearly molten as recently as twenty million years ago. Geologists countered that the formation of some rock deposits must have taken at least twenty times as long—four hundred million years. Backed, not by theory, but by a vast accumulation of observation, geologists doubted the physicist’s theories. Kelvin had assumed that Earth had been created as a completely molten ball of rock, and determined the amount of time it took for the ball to cool to its present temperature. His calculations did not account for the ongoing heat source in the form of radioactive decay, which was still unknown at the time.

In 1897 J. J. Thomson experimentally discovered the electron. At about the same time, however, the same experiment was done by Walter Kaufmann. The main difference between their experiments was that Kaufmann’s was better, yielding a ratio of the electron’s charge and mass that today we know was more accurate than Thomson’s. But Kaufmann is not listed as a discoverer of the electron, because he did not think he had discovered a new particle. Kaufmann was a positivist and did not believe that physicists should speculate on things they could not observe. So, he did not report that he had discovered a new kind of particle, but only that whatever flowed in a cathode ray tube carried a certain ratio of electric charge to mass.

In 1905 the French mathematician Henri Poincaré independently discovered the same space-time transformations as Einstein. But, to Poincaré, they were just mathematical concepts, with no physical significance. Einstein, on the other hand, took the physics seriously and developed the Special Theory of Relativity which is thus credited to him alone.

In 1910, after atomism had been widely accepted, Ernst Mach wrote to Max Planck that “if belief in the reality of atoms is so crucial, then I renounce the physical way of thinking. I will not be a professional physicist, and I hand back my scientific reputation.” Planck didn’t believe in atoms, either, and invented his own convoluted theory to assure himself that they did not exist.

On Nov 6, 1919 there was a joint meeting of the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society in London where the Astronomer Royal announced that Einstein’s theory had been verified. J. J. Thomson said that relativity had now to be reckoned with and that our conceptions of the fabric of the universe must be fundamentally altered. At this point the eminent astronomer Sir Oliver Lodge rose and walked out of the meeting. Ideas that require people to reframe their picture of the world provoke denial and hostility. It is no different in science, than it is in politics or religion.

These were all men who acted out of a scientific orientation grounded in their individual psychology. Thomson was willing to speculate, Kaufmann was not. Planck and Lodge could not adjust to a potentially new reality. Perhaps the most explicit example would be 19th-century physician and experimental psychologist H. L. F. von Helmholtz. When asked about the possibility of telepathy, he said: “Neither the testimony of all the Fellows of the Royal Society, nor even the evidence of my own senses, would lead me to believe in the transmission of thought from one person to another independent of the recognized channels of sense.” Even Albert Einstein, who single-handedly initiated the 20th century revolution in physics, could not to his dying day accept what quantum physics said about the world.

As physicist Heinz Pagels wrote:

“Why did Einstein reject the interpretation of the new quantum physics—when most of his fellow scientists accepted it? Any answer to this question cannot be simple. Einstein’s rejection reflects not just his rational choice but also the roots of his personality and character formed during his childhood in Germany. By examining his childhood we find clues to his later persistent adherence to the classical world view.”

What can all this mean? Astrophysicist John Bahcall at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton said:

“I personally feel it is presumptuous to believe that man can determine the whole temporal structure of the universe, its evolution, development and ultimate fate from the first nanosecond of creation to the last 1010 years on the basis of three or four facts which are not very accurately known and are disputed among the experts. That I find, I would say, almost immodest. So I don't take those models very seriously. That doesn't mean that I don't publish papers based upon them, but it does mean that I tend to regard them pretty much the same way that I would regard Newton's theology. An interesting intellectual exercise, but nothing to be worried about.”

The soundness of Ant/Human cosmology would be a matter of opinion because its foundation would rest on unverifiable assumptions. This is why some physicists can believe in the Big Bang origin of the universe while others, like Nobel laureate Hannes Alfven and cosmologist Sir Fred Hoyle, could not.

Science, and the assumptions of the so-called scientific method, dominate Western culture. This would be unremarkable if science were open-ended and unlimited in terms of its potential. But it is not. Technology is the practical side of science and, because there have been such incredible accomplishments, from the steam engine to satellite communications to micro-miniaturized medicine, and nanotechnology, science is regarded as unassailable.

Harvard cosmologist Sheldon Glashow, however, describes the basic insubstantiality of science:

"We believe that the world is knowable, that there are simple rules governing the behavior of matter and the evolution of the universe. We affirm that there are eternal, objective, extrahistorical, socially neutral, external and universal truths and that the assemblage of these truths is what we call physical science. Natural laws can be discovered that are universal, invariable, inviolate, genderless and verifiable…. This statement I cannot prove, this statement I cannot justify. This is my faith."

Where do we go from here? MIT physicist Heinz Pagels wrote: "While deeply held beliefs should not contradict science, they also cannot be founded on science."

I believe that science in its current form, as a method of exploring and understanding reality, has come as far as it can. This is not to disparage or discard science. Its handmaid, technology, still has a long run ahead. But science itself has come to explain and explore more and more about less and less.

Essayist J. B. Priestley gives us a perspective on the harm that science has done to our society:

“It is our Life-shrinkers who have been busy as long as I can remember just sealing us down and then squeezing the juice out of us. We quit their company feeling like desiccated dwarfs. The most important of them have been lop-sided ‘nothing but’ men on the very highest and most imposing level. And to prove I am not dealing in vague abuse, I will stick my neck out as far as it can go. Among the very greatest names of the last hundred years, those men whose influence can hardly be over-estimated, are Marx, Darwin and Freud. And with all due respect for their personal qualities, I say that all three of them, working in their very different fields, have been Life-shrinkers”.

As Sir James Jeans summed it up: “The history of physical science in the twentieth century is one of progressive emancipation from the purely human angle of vision.”

”Leningen versus the Ants”

I first read this story in high school and I’ve never forgotten it. It’s about Leningen who has a plantation in Brazil. Here is one of the opening paragraphs:

The Brazilian official threw up lean and lanky arms and clawed the air with wildly distended fingers. "Leningen!" he shouted. "You're insane! They're not creatures you can fight—they're an elemental—an 'act of God!' Ten miles long, two miles wide--ants, nothing but ants! And every single one of them a fiend from hell; before you can spit three times they'll eat a full-grown buffalo to the bones. I tell you if you don't clear out at once there'll be nothing left of you but a skeleton picked as clean as your own plantation."

You can read the story here: classicshorts.com/stories/lvta.html

Daniel Johnson was born near the midpoint of the twentieth century in Calgary, Alberta. In his teens he knew he was going to be a writer, which is why he was one of only a handful of boys in his high school typing class — a skill he knew was going to be necessary. He defines himself as a social reformer, not a left winger, the latter being an ideological label which, he says, is why he is not an ideologue. From 1975 to 1981 he was reporter, photographer, then editor of the weekly Airdrie Echo. For more than ten years after that he worked with Peter C. Newman, Canada’s top business writer (notably on a series of books, The Canadian Establishment). Through this period Daniel also did some national radio and TV broadcasting. He gave up journalism in the early 1980s because he had no interest in being a hack writer for the mainstream media and became a software developer and programmer. He retired from computers last year and is now back to doing what he loves — writing and trying to make the world a better place

Daniel Johnson was born near the midpoint of the twentieth century in Calgary, Alberta. In his teens he knew he was going to be a writer, which is why he was one of only a handful of boys in his high school typing class — a skill he knew was going to be necessary. He defines himself as a social reformer, not a left winger, the latter being an ideological label which, he says, is why he is not an ideologue. From 1975 to 1981 he was reporter, photographer, then editor of the weekly Airdrie Echo. For more than ten years after that he worked with Peter C. Newman, Canada’s top business writer (notably on a series of books, The Canadian Establishment). Through this period Daniel also did some national radio and TV broadcasting. He gave up journalism in the early 1980s because he had no interest in being a hack writer for the mainstream media and became a software developer and programmer. He retired from computers last year and is now back to doing what he loves — writing and trying to make the world a better place

Articles for March 9, 2010 | Articles for March 10, 2010 | Articles for March 11, 2010

Quick Links

DINING

Willamette UniversityGoudy Commons Cafe

Dine on the Queen

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

MUST SEE SALEM

Oregon Capitol ToursCapitol History Gateway

Willamette River Ride

Willamette Queen Sternwheeler

Historic Home Tours:

Deepwood Museum

The Bush House

Gaiety Hollow Garden

AUCTIONS - APPRAISALS

Auction Masters & AppraisalsCONSTRUCTION SERVICES

Roofing and ContractingSheridan, Ore.

ONLINE SHOPPING

Special Occasion DressesAdvertise with Salem-News

Contact:AdSales@Salem-News.com

googlec507860f6901db00.html

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

All comments and messages are approved by people and self promotional links or unacceptable comments are denied.

Jeff Kaye~ March 11, 2010 3:06 pm (Pacific time)

I really enjoyed this one, DJ... I'm continually amazed at the breadth and depth of your knowledge. You and Ersun have exceptional insights into your various (and very varied) fields of expertise. I think I have part, and a large part (well, not comparatively), of that vast Argentine ant colony on my little acre of ground. I'm not sure where they came from; down here in Texas we call them fire ants. Because their sting and bites burn like fire. I had heard that they arrived by boat in Louisiana, and spread rapidly across the South from there. These ants are ferocious. They've been known to kill and eat young deer when they're unlucky enough to be born near an ant mound. My older brother (he was 5 and I was 4) was once overcome by them. He was rooted in place, screaming in pain, as they swarmed up his legs, biting and stinging both with their mandibles and tail stingers, it looked like. Picture little brown wingless wasps. I swatted most of the ants off his legs, and pushed him to get him off their mound. I might have saved his life, but he claims he doesn't remember it that way at all. He says it was the other way around, that I was the one being stung. He has a bit of a memory problem, (or do I?)... The memory is vivid for me, yet I am constantly stung by these damn things while trying to do any yard work. They're literally EVERYWHERE under the surface of the topsoil. I don't like to put poison out, as I like to feed the birds. Plus, when it rains, that poison runs off into the water table. Speaking of birds, these ants will often kill baby birds in their nests, transporting them bite by bite back to their farm. But back to your story... Some may criticize your math, and while I thought it may've been off on a decimal point or two, that's completely missing the point of the story, which I believe was aabout perspective. If we don't change the way we look at and think about things, and soon, the ants won't have to worry about us for much longer. We're rapidly destroying the environment; making it unlivable for humans, but the ants will still be thriving long after our last pitiful gasp. How much more efficient, thrifty and successful a species we could be, with a tenth of the social/communication skills of these tiny powerhouses. While I'm no great thinker, it doesn't take a genius, or even a scientist, to see that if we don't stop breeding like rodents and consuming resources like it's our last year on Earth, it soon will be.

Thanks for your comments, Jeff. It's one thing I've thought of about living here in southern Canada--temperate zone. We don't have any real pests like you would have in the southern US where they can live year round. I don't even know the names of most of your pests because I have no experience of them. Chiggers, come to mind, whatever they are. No scorpions, etc. I've got more what I hope will be interesting things in the works.

Vic March 11, 2010 9:07 am (Pacific time)

"Put another way, it is the assumptions that we hold, consciously and unconsciously, that are the filter through which we interpret the world we “see”. Truer words were never spoken. If there is a "Secret of the Universe", I believe that is it. And as a life-long myrmeophile, I have constantly been amazed by the intelligence shown by ants. I had at one time, a large 3'x 5' "antfarm" and was able to experiment with ants...I came to the conclusion that there appears to be a "colony consciousness" ...events in one area would trigger similar immediate responses throughout the complex. Much of this of course has to do with scent and chemical "signals". Unlike the Argentine ants mentioned, Oregon's Formic or Wood ants will attack other Formic ants if not from the same anthill. I tried introducing larvae from a different nest..the nurse ants would try to get them down into the nursery, but the soldier ants would puncture the larvae. Some of you younger readers may remember me as "The Ant Man", as I used to take my ant farm to elementary schools and do presentations. I suspended the ant farm inside my van so I could transport it without collapsing the tunnels....Also the Biblical exhortation to work and save like the ant is somewhat incorrect. Most ants do not save up or store food. The Harvester ants of the American SW are an exception..these are the kind one gets with a commercial ant farm. Enjoyed this article !

Tony Orman March 11, 2010 8:34 am (Pacific time)

I came across Daniel Johnson’s article while trawling through the Internet, as one does. I was astonished by the breadth of its reach across the whole theory of science itself and the conflicting beliefs in science, technology and world philosophy. But I feel that Mr. Johnson is making the same philosophical error that he blames on others. Consider two of his points in this article. First, he quotes from statements by Lord Kelvin, Ernest Rutherford, Ernst Mach and Max Planck to show that what they said in one generation was proved wrong in the next generation. Then he goes on to say: “I believe that science in its current form, as a method of exploring and understanding reality, has come as far as it can. This is not to disparage or discard science. Its handmaid, technology, still has a long run ahead. But science itself has come to explain and explore more and more about less and less.” In these three sentences he leaves himself wide open to the possibility that the next generation of scientists will make huge discoveries equally as broad as nuclear and quantum physics appear to us today.

Sorry, Tony, but I wasn't clear. I was talking about assumptions that scientists hold that lead them astray. That's a human trait, overall, though. Whatever may be discovered in the near or mid-future is not only unknown, but we can't even speculate about it. But the real advances, the progress, is through technology, not science. Half or more of our economy comes from technology based on quantum physics. But no one understands quantum physics. As Nobel physicist Richard Feynman put it: “I think it is safe to say that no one understands quantum mechanics. Do not keep saying to yourself, if you can possibly avoid it, ‘But how can it be like that?’ because you will go ‘down the drain’ into a blind alley from which nobody has yet escaped. Nobody knows how it can be like that.”

Ersun Warncke March 11, 2010 7:15 am (Pacific time)

"I believe that science in its current form, as a method of exploring and understanding reality, has come as far as it can." --- I agree that attempting to craft a consistent universal explanation of reality based on science is a fool's errand. The scientific method was never intended for that purpose, and could never achieve that end. However, individuals using the scientific method to explore reality from their own perspective provides discovery without end. Something to note is that any theory is just one person's perspective. Convincing a bunch of other people of its veracity does not broaden its scope one bit. Science that revolves around proving this and disproving that is self-narrowing because it is essentially a popularity contest where people are trying to get as many other people behind them to say that they are the smartest. This is a waste of time for all involved, and is not real science, which would be all of those people going out and exploring reality for themselves and forming their own perspectives.

Good points, Ersun. That reminds me of a quote by science writer Kitty Ferguson commenting on large teams of scientific researchers.

"When the difficulty of the experiments is combined with the social dynamics of large teams, things get very far from high school science. To take just one question, raised by the historian of science Peter Galison: How does a large collaboration decide when an experiment is finished? Do they vote? That seems hardly good enough-scientific truth is not a matter of the view of the majority. But if consensus is sought, what about the few cautious holdouts who will always insist on waiting for more data before announcing a result? And should we worry that the group may be more likely to embrace an analysis of the data that agrees with what the theorists want than one that disagrees?"

And, of course, scientific truth is the view of the majority. Just take the case of Alfred Wegener. He discovered and argued for continental drift in 1912. He was rejected and ridiculed by the majority of geologists. Continental drift was not generally accepted until the 1970s, long after his death.

"As recently as 1974, at St. John’s College in Cambridge, England," says neuroscientist V. S. Ramachandran, "a professor of geology shook his head when I mentioned Wegener. ‘A lot of rot,’ he said with exasperation in his voice.”

Daniel Johnson March 11, 2010 4:03 am (Pacific time)

Mr Hodge: Thank you for your insightful comments. This article is a continuation of sorts from two previous pieces. You (and other interested readers) might want to read them and come back with new criticisms.

"A Life-Shrinker's Roll-call" (Oct 21/09)http://www.salem-news.com/articles/october212009/life_shrinkers_dj.php

"Descartes' Disaster" (Nov 19/09) http://www.salem-news.com/articles/november192009/disaster_dj.php

You can comment there, or here. I'll see them either way and can respond.

But first, a response to your one criticism about surface area:

I was using a simple thousand to one ratio. I was going for effect, rather than accuracy. The surface area of a sphere is = 4(pi)r2. The radius of the earth is approximately 4,000 miles. So, on a thousand to one ratio, the radius from an ant's perspective would be 4,000,000 miles and the surface area would be approximately 200 trillion square miles. Analogies can be slippery things. Thanks for pointing that out.

Russ Hodge March 11, 2010 1:18 am (Pacific time)

One more comment. " believe that science in its current form, as a method of exploring and understanding reality, has come as far as it can. This is not to disparage or discard science. Its handmaid, technology, still has a long run ahead. But science itself has come to explain and explore more and more about less and less." and "Among the very greatest names of the last hundred years, those men who influence can hardly be over-estimated, are Marx, Darwin and Freud. And with all due respect for their personal qualities, I say that all three of them, working in their very different fields, have been Life-shrinkers”. Well, it's a fun point of view (philosophically), but it represents a pretty horrible oversimplification of science (particularly in regard to Darwin). Darwin's work opened thousands of fruitful new avenues for exploring the world that simply weren't possible within the prior philosophical framework ("Natural Theology," aka intelligent design), which is an inquiry-blocking view of the world. If we did arrive here through a process of evolution - which has been substantiated in countless ways - then we must find a healthy way to live with each other within an ethical framework that is pluralistic and likely agnostic. Anything else is simply denial, and statements like those above block valuable human qualities like curiosity and discovery, rather than promoting them.

Russ Hodge March 11, 2010 1:09 am (Pacific time)

I would like to take issue with some points from this interesting article. First, I think (although it's a bit hard to tell) that the sentence "The earth’s surface area (land, water and ice) is about 200 million square miles. From an ant’s perspective that would be about 200 billion square miles," represents a miscalculation... it's true that in the linear calculation of measurements, 1 mile = 1,000 miles, but when you're talking about surface area that has to be squared: 1 square mile = 1 million squared thousandths of a mile, so the surface area should probably be 200 trillion rather than 200 billion... but perhaps the author is using the British meaning of billion. Secondly, the statement "Where do we go from here? MIT physicist Heinz Pagels wrote: "While deeply held beliefs should not contradict science, they also cannot be founded on science," obviously comes from a physicist rather than a biologist. Significant, world-changing new concepts are emerging all the time from modern biology, and that process is likely to continue well into the future. Our understanding of the biological and material side of human existence is still in its infancy - for two examples: the attempt to explain phenomena like consciousness in terms of molecules and gross brain structures; and the attempt to fight cancer and complex diseases through the manipulation of the immune system. These two fields will undergo "mind-blowing" changes in the coming decades, and they will alter our understanding of human nature just as the theory of evolution did. Since science is a human enterprise, it is ultimately based on a deep understanding of our biology, and scientists in other fields do not at all share your opinion. It's not surprising that some physicists feel this way, because they're working in a field where "great experiments" come every 15 or 20 years (or even more). In biology they happen every day.

[Return to Top]©2026 Salem-News.com. All opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Salem-News.com.